Onchocerciasis (River Blindness)

Key points

- Onchocerciasis is a disease caused by the filarial nematode (worm) Onchocerca volvulus, found mainly in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Onchocerciasis can affect the eyes, skin, and lymph nodes.

- It is a significant cause of blindness globally, and is also known as “river blindness”.

- It can present with skin pruritus (itching), rash and/or subcutaneous nodules, and can progress to permanent skin damage.

- More rarely, it causes lymphadenopathy or unilateral limb edema.

- Because the incubation period can be up to 4 years, onchocerciasis may present in children and youth several years after their arrival in Canada.

- Diagnosis can be made by skin snip, slit lamp examination for eye involvement, or serology.

- Treatment is ivermectin every 3-6 months for an extended period. Doxycycline may be added. Consultation with infectious disease and ophthalmology specialists is recommended.

Introduction

Onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness, is a filiarial disease caused by the nematode (worm) Onchocerca volvulus. It is transmitted by infected blackflies of the Simulium species that live along fast-flowing water.1 Adult female worms can live under the skin in a human host for up to 15 years, producing many prelarval microfilariae which disseminate and can survive for 2 to 3 years.2 Most consequences of this infection relate to the immune response to dead or dying microfilaria in the skin and eyes. A heavy microfilarial load can result in intense itchiness of the skin that can become severely excoriated and disfiguring. Microfilaria in the eyes can cause visual impairment and, if left untreated, can lead to blindness.

Epidemiology

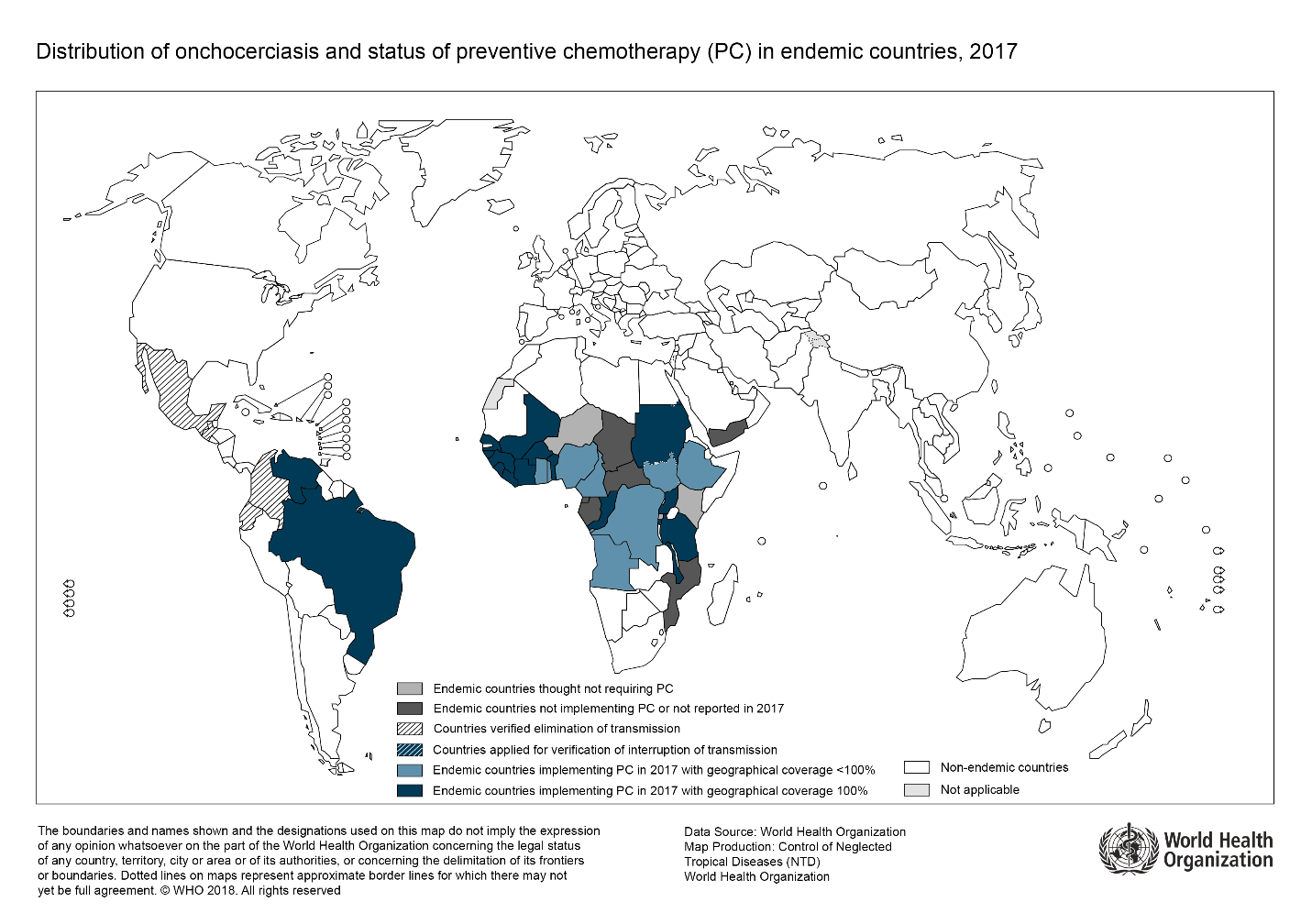

The epidemiology of Onchocerciasis has changed over recent decades, as public health strategies have suppressed or eliminated the disease in many regions. However, in 2017 there were still an estimated 20.9 million infections globally, including 14.6 million individuals with dermatological manifestations and 1.15 million with vision loss.3 Onchocerciasis is the second-most common infectious cause of blindness, after trachoma. The vast majority of infections occur in 31 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, with a small number of cases Yemen, Venezuela, and Brazil.1

Figure 1 shows high risk regions, including areas targeted with preventive chemotherapy campaigns.

| Figure 1. Distribution of onchocerciasis and status of preventive chemotherapy (PC) in endemic countries, 2017 |

|

| Source: Reproduced, with the permission of the publisher, from “Onchocerciasis (river blindness)”, Geneva, World Health Organization: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/onchocerciasis, accessed Jan 29, 2021. |

The prevalence in young newcomers to Canada is not known. Imported onchocerciasis in migrants and travelers is thought to be rare, and rates should decrease further with improved global control. Small case series have been published,4-8 which include some adolescents. However, onchocerciasis is likely underdiagnosed,9 as physicians in non-endemic regions are unfamiliar with this infection5 and symptoms can be chronic, low-grade, and non-specific.

Risk factors

People who live in rural areas near fast-flowing rivers and streams in an endemic region (especially Sub-Saharan Africa) are at highest risk of infection.1 Infection can occasionally be acquired during a brief (1 month) stay in a highly endemic area.7

Clinical presentation

Onchocerciasis may remain asymptomatic, or progress to various clinical manifestations. Incubation period is 1-2 years on average, but can be as long as 4 years.4 Given the potential for serious and preventable morbidities including blindness, it should be suspected in patients with a compatible migration or travel history, and any of the following symptoms:1,9,12

DERMATOLOGIC:

- Pruritus (itchiness): Varying severity. May last for years.

- Rash: Typically acute or chronic papular dermatitis.

- Subcutaneous nodules (inhabited by adult worms).

- Complications: Pruritis can lead to insomnia, depression, severe excoriation with hypertrophy, and secondary bacterial skin infections. Long-term skin sequelae include hyperpigmentation, lichenification, atrophy (thinning of the skin with loss of elasticity) and depigmentation (“leopard skin”, especially on the lower legs).

OCULAR:

- Mild: Itching, dryness, red eyes, photophobia, punctate keratitis (reversible)

- Severe: Sclerosing keratitis (irreversible), iridocyclitis, uveitis, chorioretinitis, optic neuritis

- Complications (if untreated): Corneal clouding, cataracts, glaucoma, optic atrophy, blindness

- Visit Vision Screening for more information on assessing young immigrants and refugees new to Canada.

LYMPHATIC: (uncommon)

- Non-painful swelling of lymph nodes.

- Unilateral limb edema.

NEUROLOGIC:

- There is controversy over whether volvulus can trigger epilepsy in children, including Nodding Syndrome characterized by atonic neck seizures.10

Limited data suggest that migrants from endemic areas are more likely to present with subcutaneous nodules, skin depigmentation and atrophy, and eye disease, while travelers more often have papular dermatitis and unilateral limb edema.7.8 These differences may relate to chronicity of infection.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of onchocerciasis can be made by detection of an adult worm in an excised skin nodule; observing live microfilaria in a skin snip biopsy or in the anterior segment of the eye on slit lamp exam; or positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on skin snip biopsy.9

As the above investigations may be inaccessible in non-endemic areas and can have limited sensitivity, serology is often used. The serological assay available at the National Reference Centre for Parasitology in Montreal detects multiple filarial parasites, but a positive result is supportive in the appropriate clinical context. Newer serological assays based on specific O. volvulus antigens have increased sensitivity9 but are not currently available in Canada.

If onchocerciasis is suspected, an ophthalmology consultation should be requested for diagnosis and detection of complications.

Eosinophilia and high IgE are often present (2/3 of patients in one case series8), but their absence should not rule out Onchocerciasis if clinically suspected.

Treatment

Treating onchocerciasis is crucial to prevent long-term skin damage and blindness. Consulting with an infectious diseases specialist and ophthalmologist in all cases is recommended.

Infection is treated with ivermectin, an anti-parasitic agent now approved for use in Canada. Ivermectin kills microfilariae and temporarily halts microfilariae production by adult worms. However, ivermectin does not effectively kill the adult worms. It is given every 3-6 months for the duration of symptoms or the expected lifespan of the adult worm (10-15 years)1,9,11,12

Doxycycline for 4-6 weeks may be added to ivermectin to kill the adult worm. Doxycycline targets the endosymbiotic bacteria Wolbachia, which is essential to adult worm survival. A randomized controlled trial in Ghana showed that addition of doxycycline to ivermectin significantly decreased microfilarial and adult worm load in onchocerciasis patients with suboptimal response to ivermectin13, though effects on long-term outcomes remain unknown.

Ivermectin is generally safe and well-tolerated. The most common side effect is GI upset. Less often, Mazzotti reaction (pruritis, rash, or conjunctivitis in response to microfilarial killing), facial edema, or orthostatic hypotension can occur. The safety of treating children under 15 kg has not been demonstrated.12 Importantly, ivermectin can precipitate a severe encephalopathy in individuals with heavy co-infection with loa loa (another filarial parasite). Patients from loa loa-endemic regions in West and Central Africa should have blood smears tested for loa loa prior to ivermectin treatment.

Doxycycline can cause GI upset, photosensitivity, and teeth staining in fetuses/young children. It is contraindicated in pregnancy and should be used with caution in young children, though doxycycline is now considered safe for short durations (< or = 21 d) in children < 8 yrs.

A novel anti-parasitic agent, moxidectin, has shown promise in a recent trial14 but is not currently available for clinical use in Canada.

Prevention

At present, there is no vaccine against onchocerciasis. Personal protective measures to prevent insect bites should be used when visiting endemic regions. More information about such precautions can be found in the Travel-related Illness section.

References

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheets: Onchocerciasis.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Onchocerca volvulus. Pathogen safety data sheet — infectious substances. Ottawa, ON: PHAC; 2011.

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018 Nov 10;392(10159):1789-1858.

- Antinori S. Is imported onchocerciasis a truly rare entity? Case report and review of the literature. Travel Med Infect Dis. Mar-Apr 2017;16:11-17.

- Enk CD, et al. Onchocerciasis among Ethiopian immigrants in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003 Jul;5(7):485-8.

- Develoux M, et al. Imported filariasis in Europe: A series of 31 cases from Metropolitan France. Eur J Intern Med. 2017 Jan;37:e37-e39.

- Lipner, EM. Filariasis in travelers presenting to the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2007 Dec 26;1(3):e88.

- Showler AJ, et al. Differences in the Clinical and Laboratory Features of Imported Onchocerciasis in Endemic Individuals and Temporary Residents. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019 May;100(5):1216-1222.

- Showler AJ, et al,. Imported onchocerciasis in migrants and travelers. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018 Oct;31(5):393-398.

- Gumisiriza N, et al. Changes in epilepsy burden after onchocerciasis elimination in a hyperendemic focus of western Uganda: a comparison of two population-based, cross-sectional studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Nov;20(11):1315-1323.

- Gardon J, et al. Effects of standard and high doses of ivermectin on adult worms of Onchocerca volvulus: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002 Jul 20;360(9328):203-10.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites –Onchocerciasis (also known as River Blindness): Resources for health professionals.

- Debrah AY, et al. Doxycycline Leads to Sterility and Enhanced Killing of Female Onchocerca volvulus Worms in an Area With Persistent Microfilaridermia After Repeated Ivermectin Treatment: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Aug 15;61(4):517-26.

- Opoku NO, et al. Single dose moxidectin versus ivermectin for Onchocerca volvulus infection in Ghana, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a randomised, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018 Oct 6;392(10154):1207-1216.

Editor(s)

- Laura Erdman, MD

- Susan Kuhn, MD

Last updated: February, 2023