Prenatal Risk Factors for Developmental Delay in Newcomer Children

Key points

- Developmental disabilities can occur singly or concurrently in one person. They might involve a cognitive or sensory difficulty, social or communications/language-related problem, a motor impairment, adaptive delay or some combination of these.

- 10% to 20% of individuals have some kind of developmental disability.

- Prenatal risk factors include chronic maternal illness, certain maternal infections, toxin exposures and nutritional deficiencies.

- Risk factors in the perinatal period include pregnancy-related complications, prematurity and low birth weight, and infection exposure during pregnancy or at time of birth.

- Lack of access to quality care during pregnancy, delivery and soon after birth can significantly, adversely affect outcomes for both mother and child, including contributing to developmental disabilities.

- The lack of maternal and child health care is a significant problem in developing countries. Lack of health insurance and inadequate access to health care for newcomers in Canada could similarly adversely affect health outcomes.

Causes of developmental disabilities

Developmental disabilities can involve a cognitive or sensory difficulty, social or communications/language-related problem, a motor impairment, adaptive delay or some combination of these. The Global Disease Control Priorities Project estimates that 10% to 20% of individuals worldwide have a developmental disability of some kind.1 In the U.S. alone, it is estimated that 9% of children younger than 36 months of age have a possible developmental problem,2 while 13.87% of children 3 to 17 years of age have a developmental disability.3

Health care providers who see newcomer families have a pivotal role to play in identifying and initiating early treatment for developmental disabilities. As child or family advocates, we communicate not only with family members but with related health services, including community programs and supports. See Child Development: Issues and Assessment and Community Resources Serving Immigrant and Refugee Families for links to supportive first-line provincial/territorial agencies and services.

Developmental disabilities may last a lifetime but early recognition of their existence, a timely diagnosis and an appropriate treatment plan can make a difference for the children and families involved. When seeing newcomer families, recognize that risk factors are cumulative. In many parts of the world, suboptimal conditions and care during pregnancy and childbirth can have a range of impacts on developmental health.

- Consider the spectrum: risks common in developing countries, specific to this family’s country of origin, and factors that are family- or ethnicity-specific.

- Be ready for diverse attitudes about developmental disabilities. More information about cultural perspectives on developmental disability is available in this resource.

- Respond quickly and sensitively to early signs of a developmental disability. A timely intervention will improve developmental outcomes and the family’s adjustment.

Developmental disabilities in immigrant and refugee children do not always have a known cause. Common prenatal and perinatal risk factors to consider when taking a patient or family history are reviewed here. Information and approaches for conducting a culturally sensitive patient history are available on this website.

Prenatal risk factors include:

- Preconceptional factors

- Infections

- Exposure to toxins

- Maternal chronic illness

- Maternal nutritional deficiencies

Perinatal causes may include:

- Pregnancy-related complications

- Infections

- Rh isoimmunization

- Prematurity and low birth weight

Prenatal risk factors

Preconceptional factors

Preconceptional causes of developmental disability relate predominantly to genetic disorders or malformation syndromes. Genetic disorders are the most commonly identified causal factor for intellectual and other disabilities, and include single gene disorders, multifactorial and polygenic disorders, and chromosomal abnormalities. Genetic disorders associated with developmental delay include aneuploidies and inborn errors of metabolism. Consanguinity increases the prevalence of rare genetic disorders and significantly increases the risk for intellectual disability and serious birth anomalies, especially in first cousins. Some ethnic communities (e.g., Ashkenazi Jews) have a higher prevalence of rare genetic mutations and congenital anomalies affecting development.4

Causes of intellectual disability can be divided into the following categories, listed here with their associated prevalence:1

- chromosomal abnormalities (30%)

- central nervous system malformations (10% to 15%)

- multiple congenital anomalies syndromes (4% to 5%)

- metabolic (3% to 5%)

- acquired (15% to 20%)

- unknown (25% to 38%)

Prenatal infections

When taking a patient history for a newcomer child with signs of developmental disability, health care providers need to consider the following infections, and screen accordingly. Women who are pregnant and new to Canada must be screened for HIV, syphilis and rubella. The results of this information need to be communicated to the infant’s health care provider.

HIV

Children younger than 14 years of age are rarely screened for HIV before arriving in Canada, and may not have been tested even if their mother was known to be infected. Maternal HIV increases the risks for prematurity and being small for gestational age (SGA); both effects are associated with increased risk of mortality and developmental delay. HIV enters the central nervous system days to weeks after primary exposure. The virus causes neuronal damage and cell death, leading to progressive encephalopathy with motor disabilities, as well as to microcephaly and brain atrophy, with cognitive and language delays. More information on HIV/Aids and newcomer children is available in this resource.

The effects of being exposed to but not infected by HIV in utero, or of exposure to perinatal antiretroviral therapy, remain unclear. While preliminary U.S. and European studies have been encouraging, studies in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia indicate that a large proportion of such children have global developmental scores below their population mean for language and behaviour. However, suboptimal maternal health, malnutrition, concurrent illness and high viral loads can also negatively affect a child’s developmental potential.5

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

In the developed world, CMV is the most common congenital viral infection, with an overall prevalence of 0.6%.6 Ten per cent of affected infants show signs of infection at birth, with a substantial risk of neurological sequelae such as sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), intellectual delay, microcephaly, seizure disorders and cerebral palsy. CMV is the leading nonhereditary cause of SNHL, which may be progressive, absent at birth, unilateral or bilateral. More information on hearing screening for newcomer children is available in this resource. Both hearing loss and visual problems can occur in an otherwise asymptomatic infant.

CMV is a herpes virus spread by close interpersonal contact with saliva, blood, genital secretions, urine or breast milk. Maternal transmission to the fetus from a new or reactivated infection can occur at any gestational age but is highest with a primary infection compared to a reactivated infection.

There are geographical variations among virus strains and higher CMV rates in South America, Africa and Asia, and lower rates in Western Europe and the U.S. CMV occurs more frequently in nonwhites and individuals living in poverty.6

Toxoplasmosis

Congenital toxoplasmosis occurs at a rate of 1.5 cases per 1000 live births and causes neurocognitive deficits such as intellectual disability, seizures and visual impairment caused by chorioretinitis. Toxoplasma gondii is a parasite and a food-borne pathogen. Human infection results from ingesting or handling undercooked or raw meat containing cysts, by direct contact with infected cats or by consuming food or water contaminated by oocytes (egg cells) from infected cat feces. Higher rates of infection occur in South America, the eastern Mediterranean and parts of Africa.7

Rubella

There are an estimated 110,000 cases of congenital rubella annually worldwide. Maternal infection during pregnancy transmits the rubella virus to the fetus, causing deafness, congenital cataracts, microcephaly, seizures, intellectual disability, autism, diabetes, and thyroid dysfunction.4

Making sure that women new to Canada are screened for rubella and immunized before pregnancy prevents congenital rubella syndrome.

The rubella vaccine by the end of 2017 has been introduced nationwide in 162 countries, but global coverage is estimated at 52%.8 Congenital rubella is highest in WHO Africa and SE Asia region where vaccine coverage is lowest.

Syphilis

It was estimated in 2012 that over 900,000 pregnant women were infected with syphilis resulting in approximately 350,000 adverse birth outcomes ,143,000 early fetal death/stillbirth, 62,000 neonatal deaths, 44,000 preterm/low birth weight infants and 102,000 infected infants.9,10 While most countries have antenatal syphilis screening, implementation levels vary dramatically: an estimated 30% of pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa receive testing and treatment, compared with 70% of women in Europe.9 Untreated syphilis has an adverse outcome more than 50% of the time.11 Like all the preventable STIs, syphilis has been linked to preterm labour, low birth weight and death. Congenital syphilis can cause deafness, microcephaly, intellectual disability and visual impairment through interstitial keratitis.10

Zika Virus

Zika virus has been recognized to be teratogenic and is caused by the bite of primarily Aedes mosquitoes. Patients themselves are often asymptomatic other than a rash and transmission occurs via blood products, semen and female genital secretions.12 In 2015 an outbreak in Brazil led to the recognition of Zika virus and an association of microcephaly. Since 2013 Zika outbreaks have been reported in most countries in South America, the Caribbean, Mexico, the South Pacific and the USA. Zika virus also is endemic in Africa, South Asia and SE Asia.13

Congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) is associated with microcephaly, cerebral atrophy, abnormal cortical development, callosal hypoplasia, diffuse subcortical calcifications, microphthalmia, cataracts, retinal abnormalities and congenital contractures.12,14 5-15% of infants born to women infected with Zika virus during pregnancy have Zika related complications.14 Other associated complications of pregnancy include preterm birth and spontaneous abortions. CZS should be considered for a child born since 2016 onwards with unexplained microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, ventriculomegaly or major CNS abnormality and a maternal history of travel to a Zika endemic country or sexual contact during pregnancy with a male who travelled to a Zika endemic country in the preceding 6 months.12

Prenatal toxins

The developing fetal brain is especially vulnerable to environmental toxins. The blood brain barrier is more immature and more permeable to toxins. The rapid growth of the brain during the 2nd trimester is followed by neuronal migration, differentiation, proliferation and pruning throughout early childhood. Growing cells are more vulnerable to toxins as the brain forms over a longer period than other organs.15[TB1]

Smoking

Maternal smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of placenta previa, placental abruption, and preterm labour. It also has adverse affects on fetal growth.

Alcohol

Exposure to alcohol in utero is the most common teratogenic cause of developmental disabilities, including microcephaly, cognitive disability, learning disabilities, ADHD and behavioural challenges. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) occurs worldwide in approximately 1.9 per 1000 live births.11 Alcohol causes interruption of neuronal production and secondary destruction, with faulty migration of neurons causing microcephaly.

Other drugs

Maternal exposure to other toxins, including recreational drugs and certain medications (e.g., valproic acid, phenytoin sodium, isotretinoin [Accutane]), can also cause developmental disabilities.

Phenylketonuria (PKU)

The amino acid phenylalanine is a neurotoxin to the developing fetal brain. Untreated PKU, both maternal and postnatal in the infant, causes intellectual disabilities.

Environmental toxins

Exposure to lead, mercury and chemical compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) and alcohol can be identified as a contributing cause of intellectual disability in 4% to 5% of cases.17 The dose and timing of exposures are variables in predicting neurotoxic outcomes.

Lead can cross the placenta beginning at 12 weeks gestation and accumulate in fetal tissue. Pregnant women and young children absorb more lead when ingested; up to 70% compared with 20% for the general population. Once in the body, lead is distributed to the brain, kidney, liver and bones. Storage in teeth and bones accumulates over time and may be remobilized during pregnancy.18 Undernourished children are more susceptible to lead because their bodies absorb more lead if other nutrients such as calcium are lacking.

Dependent upon level of exposure lead can lead to reduced IQ, behavioural changes such as reduced attention span, increased antisocial behaviour and reduced educational attainment.18 Natural exposure occurs in soil but pollution, leaded gasoline, paint products, pesticides and industrial activity can raise lead levels in the air, soil and water sources.17 In developing countries there are fewer pollution controls and the use of older ceramics and some traditional medicines also increase the exposure to toxins such as lead. More information on lead exposure and newcomer children is available in this resource.

All forms of mercury can cross the placenta and be transported into fetal blood. The most common cause of prenatal mercury poisoning is eating fish and shellfish species known to contain higher levels of mercury during pregnancy.17 Other potential exposures in the developing (and developed) world are mining (especially gold mining), some industrial processes, coal plants and using products that contain mercury. The WHO provides information online about the health effects of mercury.

Arsenic is naturally present in high levels in groundwater, which can contaminate water used for drinking, preparing food and irrigating food crops. Arsenic is also present in soil, and prenatal exposure is associated from both sources with intellectual disability and developmental delay.17 The WHO provides detailed information on the early and long-term health effects of arsenic.

Developing countries are heavily reliant on agriculture for their economy and the use and disposal of fertilizers and pesticides is a serious environmental issue. Chronic pesticide exposure in the occupational setting, especially in poor rural populations, is a problem for all workers and particularly hazardous for pregnant women and children who work and live near areas where these chemicals are used.13

Prenatal exposure to the pesticide commonly known as DDT is associated with neurodevelopmental delays in early childhood. It persists in the environment for years and accumulates in the food chain and fatty tissues of humans.14 In sub-Saharan Africa, where malaria control is a significant issue, DDT use is ongoing. More information about DDT is available from the WHO.

Vignette: Unmasking a developmental delay

An apparently hyperactive 10-year-old boy is brought to your office for assessment. The family moved to Canada from Eastern Europe as refugees, and although they have been in Canada for over 6 months, they speak little French or English. Their boy was reported to be disruptive in class and was thought to have attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

A routine examination reveals poor vision in his left eye and moderately impaired vision in his right eye. This spurs a funduscopic examination that reveals severe chorioretinitis. Further questioning of the parents reveals that he had been treated for toxoplasmosis for one month when he was 2 years of age.

Follow-up investigations confirm the congenital toxoplasmosis diagnosis and severe developmental delay, even when he is tested in his mother tongue.

Learning points

- Immigrants and refugees should have visual acuity assessed soon after arrival.

- Many newcomers to Canada do not have the English or French language skills to understand medical questions or give a thorough history. Interpreters can play a crucial role in aiding communication.

- Visual and hearing impairments may mask, be confused with or occur conjointly with developmental disabilities. Information about hearing and vision screening is available in this resource.

Maternal chronic illness

Illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, renal disease and autoimmune disorders are associated with complications to pregnancy that can adversely affect a fetus or newborn child.

Maternal diabetes increases the risk of fetal anomalies, macrosomia (a birth weight >4000 grams), subsequent birth injury and hypoglycemia, all of which can negatively impact developmental outcomes in the infant. Hypertension, alone or combined with a renal or autoimmune disorder, can cause placental insufficiency and inadequate fetal growth.

Maternal nutritional deficiencies

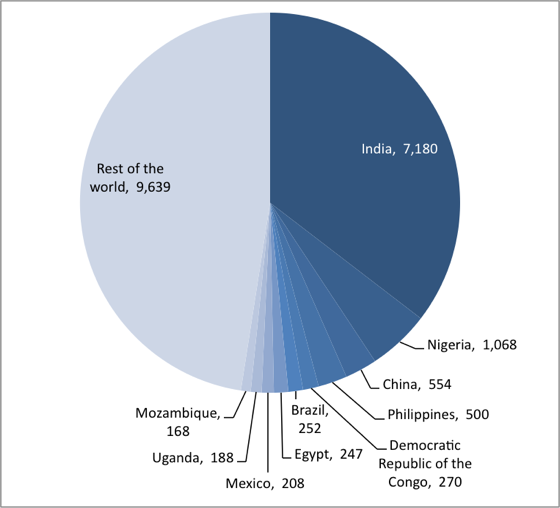

Figure 1. More than half of the world’s low-birthweight babies are in 10 countries.

Number of infants weighing less than 2,500 grams at birth (thousands), 2008─2012

Source: UNICEF global databases, 2014, based on MICS, DHS and other nationally representative surveys, 2008─2012, with the exception of India. http://data.unicef.org/index.php?section=topics&suptopicid=59

Congenital central nervous system anomalies associated with malnutrition occur more frequently in resource-constrained populations and countries. It is estimated that 94% of serious birth defects occur in middle-to-low-income countries, where mothers are more susceptible to macro- and micronutrient malnutrition. This risk factor for developmental disability may also be combined with increased exposure to prenatal toxins, infection, alcohol and poorer access to healthcare and screening.20

Folic acid deficiency is associated with neural tube defects. More information on folic acid deficiency is available in this resource. Iodine deficiency is considered by the WHO to be the leading and most preventable cause of brain damage worldwide.21 A component of thyroid hormones, iodine is essential for brain development, particularly from the second trimester of pregnancy through the third year of life. Severe deficiency is associated with intellectual disability, growth failure and cretinism. One U.K. study found that children 8 years of age were more likely to have lower scores for verbal IQ, reading accuracy and reading comprehension than their peers when their mothers had experienced only mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency in the first trimester of pregnancy.22 Iodine deficiency is an ecological phenomenon in parts of the developing world where soil erosion, the loss of vegetation due to agricultural production, the overgrazing of livestock and tree-cutting have depleted natural sources of the element.22 However, iodine deficiency can be encountered worldwide. More information on iodine deficiency is available in this resource.

Maternal malnutrition, before and during pregnancy, can have a negative impact on infant birth weight and development. Some 20 million low birth weight infants (<2500 grams) are born annually, approximately 23.8% of all births, rising to as high as 30% in many developing countries.23 Birth weight below 1500 grams is associated with a threefold increase of developmental disability.1 Read more about malnutrition and immigrants/refugee populations in this resource.

Perinatal risk factors

Health care providers need to explore pregnancy and birthing histories with newcomer mothers, with focus on experiences that may affect a child’s development. Be sure to explore these questions in an open, nonjudgmental way.

The WHO and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada define the perinatal period as commencing at 22 weeks gestation and ending 7 days after birth. The inadequate care of immigrant and refugee women in this critical period in much of the developing world puts mothers and children at higher risk for several pregnancy-related complications, such as birth trauma, hypoxia and ischemia, hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia and various serious infections.

Pregnancy-related complications

In countries where prenatal and obstetrical care are difficult to access, chronic maternal disease and pregnancy-related complications often go undetected. Conditions which, left untreated, may contribute to premature birth and/or developmental delay include:

- Gestational diabetes is associated with macrosomia, and risk of birth injury, hypoglycemia in the infant and later gestational stillbirth.

- Hypertensive disorders (e.g., pre-eclampsia and eclampsia), which can cause serious, long-term disabilities, have a higher incidence in developing countries. Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are associated with placental insufficiency and preterm delivery.

- Multigestational pregnancies have a higher rate of obstetrical complications during the pregnancy and at time of delivery.

- Birth trauma is associated with macrosomia, maternal obesity, breech presentation, operative vaginal delivery, small maternal size and maternal pelvic anomalies. Serious birth trauma (e.g., intracranial hemorrhage) is uncommon but can cause developmental disabilities. Most, but not all, neurological injuries to peripheral nerves (e.g., brachial plexus injuries) resolve over time.

Perinatal infections

- STIs: Congenital transmission of herpes viruses 1 and 2 is associated with a high risk of long-term neurological problems. Without treatment, 30% to 50% of infants born to mothers with untreated gonorrhea, and up to 30% with untreated chlamydia, will develop ophthalmia neonatorum, which can lead to blindness if not treated early. Worldwide, an estimated 1000 to 4000 babies born annually become blind secondary to ophthalmia neonatorum.10 More information on vision screening for newcomer children is available in this resource.

- Bacterial infections can be transmitted from mother to child transplacentally, during pregnancy or during delivery, by passage through the birth canal. Congenital bacterial infections leading to neonatal sepsis and meningitis are an important cause of neonatal morbidity in developing countries.

- Invasive Group B strep (GBS) occurs at an estimated rate of 0-3.06/1000 live births in developing countries24 compared to 0.24/1000 live births in developed countries.25 Invasive GBS disease is associated with long-term disabilities, including seizures, developmental disabilities and vision and hearing impairment. Important risk factors for GBS to screen for include a history of fever in labour, a preterm delivery <35 weeks, prolonged rupture of membranes >18 hours and maternal chorioamnionitis.1

- Listeria infection can occur following maternal ingestion of uncooked meats, prepared meat products and vegetables, and unpasteurized milk or foods made from unpasteurized milk. The pregnant mother may experience flu-like symptoms: fever, muscle aches, nausea and diarrhea. Transmission to the fetus causes sepsis and meningitis with subsequent sequelae. There is a higher incidence of Listeria infection in people from Latin America secondary to consumption of ‘queso fresco’ or fresh cheese.26

Rh Isoimmunization

Undiagnosed or untreated Rh isoimmunization is associated with anemia and severe hyperbilirubinemia, and may result in seizures, deafness, cognitive delays and cerebral palsy in infants who survive.

Preterm birth

| Table 1. The 10 countries with the greatest number of preterm births, 2010 | |

| India | 3 519 100 |

| China | 1 172 300 |

| Nigeria | 773 600 |

| Pakistan | 748 100 |

| Indonesia | 675 700 |

| United States of America | 517 400 |

| Bangladesh | 424 100 |

| The Philippines | 348 900 |

| The Democratic Republic of the Congo | 341 400 |

| Brazil | 279 300 |

|

Sources: WHO 19 February 2018 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth; Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. National, regional and worldwide estimates of preterm birth. The Lancet; 379(9832):2162-72. |

|

Preterm birth (<37 weeks gestation) is a global problem. Risk factors for preterm delivery include: multi-fetal pregnancy, uterine abnormalities, placental bleeding, prenatal drug exposure, chronic maternal illness, hypertensive disorders, chorioamnionitis, prolonged rupture of the membranes and bacterial vaginosis.

Lack of prenatal care, underimmunization and inadequate treatment for maternal infections or other medical issues, including STIs, can all contribute to developmental disabilities in a preterm infant.

An estimated 15 million infants are born prematurely each year, approximately 1 in every 10 births. Over 60% of preterm births occur in Africa and South Asia (Table 1). Within countries, poorer families are at higher risk.27,28

Screening for infections in pregnancy

Consider the following maternal factors when screening for infections in pregnancy:

- Fever

- Rash

- Abdominal pain

- General malaise

- Nausea with diarrhea

- Abnormal vaginal discharge

- Dysuria

- Arthritis

Conclusions

Developmental disabilities can reflect a complex constellation of problems in any child, but particularly for newcomer children, where etiology is often unclear. Sometimes a number of pre- and perinatal risk factors are involved, coexisting and having multiple, cumulative effects on developmental outcomes. Some signs of disability are evident at birth, others present as late as school age.

Developmental disabilities occur worldwide. However, the lack of access of pregnant women to sufficient, nutritious foods, and to quality prenatal, delivery and postnatal care causes significant morbidity in developing regions. Immigrant and refugees are at higher risk of developmental disabilities, with specific risk factors depending on their country of origin. Health care providers need to be mindful of general risks for all newcomers but also alert to specific patient risks, recognizing the contribution of family, immigration and ethnic history as well.

References

- Rudolph C, Rudolph A, Lister GE, et al., eds. Rudolph’s Pediatrics, 22nd edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2011.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities, 2001. Role of the paediatrician in family-centered early intervention services. Pediatrics 2011;107(5):1155-7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Developmental disabilities increasing in US: www.cdc.gov/features/dsdev_disabilities.

- WHO 19 February 2018 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rubella

- Le Doaré K, Bland R, Newell ML. Neurodevelopment in children born to HIV-infected mothers by infection treatment status. Pediatrics 2012;130(5):e1326-44.

- Swanson EC, Schleiss MR. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: New prospects for prevention and therapy. Pediatr Clin N Am 2013;60(2):335-49.

- Torgerson PR, Mastroiacovo P. The global burden of congenital toxoplasmosis: A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91(7):501-8.

- WHO 16 July 2018 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage

- WHO 3 August 2016 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis)

- WHO Guideline on Syphilis screening and treatment for pregnant women, 2017 ISBN: 978-92-4-155009-3

- WHO WHO/Global Health Observatory/map gallery syphilis(WHO 2018) Percentage of antenatal care attendees positive for syphilis www.gamapserver.who.int

- Robinson, Joan L., Zika virus: What does a physician caring for children in Canada need to know? Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases Committee. Paediatr Child Health (2017) 22 (1): 48-51

- https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/files/zika-areas-of-risk-pdf

- WHO 20 July 2018 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zika-virus

- Lanpeer, Bruce P., The impact of Toxins on the Developing Brain. Annual Review of Public Health, Volume 36: 211-23- 2015

- Abel EL, Sokol RJ. Incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and economic impact of FAS-related anomalies. Drug Alcohol Depend 1987;19(1):1951-70.

- Liu Y, McDermott S, Lawson A, et al. The relationship between mental retardation and developmental delays in children and the levels of arsenic, mercury and lead in soil samples taken near their mother’s residence during pregnancy. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2010;13(2):116-23.

- WHO 9 February 2018 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning and health

- Eskenazi B, Marks AR, Bradman A, et al. In utero exposure to dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) and neurodevelopment among young Mexican American children. Pediatrics 2006;118(1):233-41.

- WHO September 7, 2016 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/congenital-anomalies

- WHO, UNICEF, ICCIDD. Assessment of iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination: A guide for programme managers, 3rd edn. Geneva: WHO, 2008: www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/iodine_deficiency/9789241595827/en/

- Bath SC, Steer C, Golding J, et al. Effect of inadequate iodine intake status in UK pregnant women on cognitive outcomes in their children: Results from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC). Lancet 2013;382(9889):331-7.

- WHO. Feto-maternal nutrition and low birth weight: www.who.int/nutrition/topics/feto_maternal/en/

- Dagnew AF, Cunnington MC, Dube Q, et al. Variation in reported group B streptococcal disease incidence in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55(1):91-102.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ABCs Report: Group B Streptococcus, 2012: http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/gbs12.html

- Latin American Center for Perinatology, Women and Reproductive Health. Perinatal infections transmitted by the mother to her infant: Educational material for health personnel. Scientific Publication-CLAP/SMR 1567.02 December 2008.

- WHO 19 February 2018 www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard M, et al. National, regional and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. The Lancet 2012; 379(9832): 2162-72.

Editor(s)

- Cecilia Baxter, MD

Last updated: March, 2023