Enteric Fever (Typhoid Fever and Paratyphoid Fever)

Key points

- Enteric fever is an acute, life-threatening, febrile infection caused by Salmonella enterica serotypes Typhi, Paratyphi A and Paratyphi B. Each year, there are an estimated 22 million cases and 200,000 related deaths worldwide due to Salmonella typhi.

- The source of infection is food and water contaminated by the feces and urine of an acutely infected person or chronic human carrier.

- Immigrants and refugees from Southern Asia are at highest risk of enteric fever. They are also at higher risk of multi-drug-resistant infection.

- Diagnosis is made clinically and by culture. No reliable serological tests are commercially available in Canada.

- Specific antibiotic therapy shortens the clinical course of enteric fever and reduces the risk of death.

- Public health notification is required. Restrictions on child care attendance (children and staff) and food handling are regionally mandated.

Enteric fever is an acute, life-threatening, febrile infection caused by Salmonella typhi (typhoid fever) or S. paratyphi (paratyphoid fever). It is transmitted by food and water contaminated by the feces and urine of an acutely infected or convalescent person or a chronic asymptomatic carrier.

Epidemiology

An estimated 22 million cases of enteric fever and 200,000 related deaths occur worldwide each year. The risk of mortality is high (approximately 16% without antibiotic therapy), but drops to 1% with appropriate antibiotic treatment.1

Enteric fever is most common in children of school age or younger who live in endemic areas, and therefore can be concerning in young newcomers to Canada and travellers returning from high-risk areas.

Risk factors

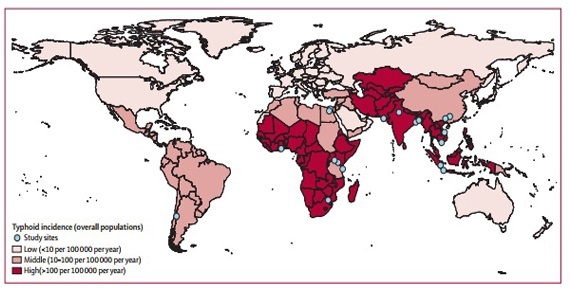

Those at risk of infection include newcomers to Canada from a high-risk area who have recently arrived (within the past 3 months) or a recent traveller to a high-risk area. Enteric fever is more common in areas of the world that have inadequate water and sanitation systems. Epidemiologic data suggests that highest-risk areas include South Asia, along with South-east and Central Asia, and Sub-saharan Africa (see Figure 1).2 A history of typhoid vaccination does not eliminate the risk of infection because vaccine protection is limited (50% to 80%).3

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of typhoid fever.

Source: Mogasale V, Maskery B, Ochiai RL, Lee JS, Mogasale VV, Ramani E, Kim YE, Park JK, Wierzba TF. Burden of typhoid fever in low-income and middle income countries: a systematic, literature-based update with risk-factor adjustment. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(10):e570–80.

It is uncommon for children to become asymptomatic chronic carriers following acute typhoid infection. If personal hygiene is poor, a chronic carrier may pose a risk for transmission to others. A chronic carrier is an individual who excretes S. typhi in stools or urine (or has repeated positive bile or duodenal string cultures) for over 1 year after onset of acute typhoid fever.

Clinical clues

The clinical presentation of enteric fever is non-specific and can range from mild illness (low-grade fever, malaise, sometimes a slight dry cough) to severe illness (severe abdominal pain, serious complications).4 The incubation period depends on the infecting dose. The usual range is 1 to 3 weeks but incubation can vary from 3 days to 3 months.

Clinical signs of enteric fever include:

- Sustained fever to 40°C

- Malaise

- Abdominal pain

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Severe headache

- Change in mental status

- Evanescent rose spots (blanching, erythematous, slightly raised lesions, especially on the trunk)

- Hepatomegaly

- Splenomegaly

- Dactylitis

Severity of infection

Complications of enteric fever usually occur during the second or third week of illness in 10% to 15% of patients. Life-threatening intestinal hemorrhage and intestinal perforation may occur in 3% of hospitalized patients with typhoid fever. Meningitis and endocarditis are rarer complications. Patients who have thalassemia or glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD) may have hemolysis during typhoid fever.

A number of factors can affect the severity and outcome of enteric infection:4

- Duration of illness before treatment

- Choice of antimicrobial treatment

- Age

- Previous exposure

- Typhoid vaccination history

- Virulence of the bacterial strain

- Quantity of inoculum ingested

- Patient characteristics, such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) type, immunosuppression (e.g., AIDS)

- Medications that diminish gastric acid (e.g., H2 blockers, antacids)

Diagnosis

Diagnosis should be considered in all febrile children who have travelled to or come from endemic areas within the past 3 months.

The best way to diagnose enteric fever is by collecting several blood cultures early in the disease. A single blood culture is positive in only half of cases. At least one stool sample should be sent for bacterial culture and sensitivity (yield is 30% to 50%). Urine culture has the lowest yield.5 Urine culture may be helpful in immigrant and refugee children who have a history of Schistosoma hematobium or tuberculosis infection of the urinary tract, which may predispose them to chronic urinary carriage after typhoid fever. Occasionally, bone marrow aspirate for culture may be necessary (yield is 90%). Leukopenia may be found.

The Widal test is a serologic assay for detecting immunoglobulins M and G (IgM and IgG) to the O and H antigens of Salmonella. The test is unreliable, however, and is not recommended in Canada. Newer serologic assays are not readily available.

Because there is no definitive serologic test for enteric fever, and cultures can be negative, the diagnosis sometimes has to be made clinically.

Management

Infection Control

Hospitalized patients diagnosed with enteric fever require contact precautions until culture results are negative for 3 consecutive stool specimens.6 Specimens must be obtained at least 48 hours after cessation of antimicrobial therapy.

Antimicrobial therapy

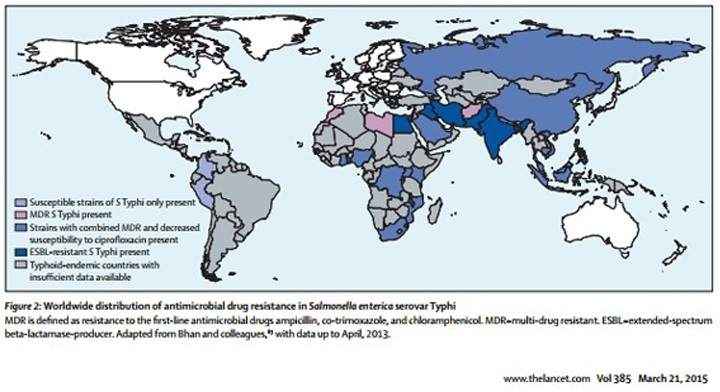

Specific antimicrobial therapy shortens the clinical course of typhoid fever and reduces the risk of death. Strains acquired in developing countries are often resistant to many antibiotics (see figure 2), but are usually still susceptible to ceftriaxone. Multidrug resistance (to ampicillin, co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol) emerged in the 1980’s, followed by reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in the 1990s and more recently sporadic cases of extended-spectrum cephalosporinase-producing strains. Resistance is most problematic in South Asia and Middle-east, but is spreading to other parts of Asia and Africa.12

Empirical parenteral ceftriaxone antibiotic therapy may be replaced with ampicillin, cotrimoxazole, azithromycin or ciprofloxacin if bacteria are susceptible, but also depends on the site of infection, the host and the clinical response. Advantages of ciprofloxacin are that for susceptible S. typhi, there is faster resolution of the fever, fewer relapses and a lower rate of stool carriage. Fluoroquinolones are not approved for use in children younger than 18 years of age. However, a potential indication for ciprofloxacin would be in multi-drug-resistant Salmonella species.2,7,8 In uncomplicated cases where Salmonella typhi or Salmonella paratyphi is resistant to ciprofloxacin, azithromycin may be the most potent oral antibiotic if the organism is sensitive.

Antibiotic treatment for 10 to 14 days is recommended for enteric fever, although shorter courses (7 to 10 days) have been effective in uncomplicated enteric fever. Meningitis should be treated for at least 4 weeks, osteomyelitis for 4 to 6 weeks.9

Figure 2: Global distribution of resistance to S. enterica serotype Typhi (to 2013). Shaded areas show disease endemicity.

Source: (From: Wain et al, Typhoid Fever, Lancet 2015;385(9973):1136-45)

Additional supportive measures

Additional supportive measures for the management of patients with enteric fever may include:4

- Oral or intravenous hydration

- Acetaminophen

- Intensive care

- Appropriate nutrition

- Blood transfusion

Corticosteroids have historically been suggested for patients with severe enteric fever, which is characterized by delirium, obtundation, stupor, coma or shock.2,5,10 However a recent review suggests the need for larger trials to confirm their utility.13

Relapse

The relapse rate is 5% to 10%, even when appropriate therapy has been given.5 Relapses typically occur 2 to 3 weeks after the resolution of fever and are milder than the initial illness. Cultures, as for the initial illness, are repeated before commencing antibiotics. The antibiotic susceptibility pattern is usually the same as during the original episode. Depending on the clinical signs and symptoms, further differential diagnosis should also be considered.

Notifying public health and exclusion

Public health authorities must be notified of cases of Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi infection and determine appropriate management of cases and contacts as mandated in that region. Children and staff in child care centres are excluded until 3 consecutive stool cultures, collected at least 48 hours after completion of antibiotic treatment, are negative.3

Prevention

Information on prevention is discussed in the Travel-Related Illness section.

Selected resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Typhoid fever.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Typhoid fever. See also the Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT), Statement on overseas travellers and typhoid. Can Commun Dis Rep 1994;20-8 (30 April 1994):1-8.

- World Health Organization. Typhoid fever.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canada Immunization Guide: Evergreen edn. See Pt. 4, Active vaccines.

- Mogasale V, Maskery B, Ochiai RL, Lee JS, Mogasale VV, Ramani E, Kim YE, Park JK, Wierzba TF. Burden of typhoid fever in low-income and middle income countries: a systematic, literature-based update with risk-factor adjustment. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(10):e570–80.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Salmonella infections. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:700.

- WHO. Background document: The diagnosis, treatment and prevention of typhoid fever. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2003.

- Parry CM, Hien TT, Dougan G, White NJ, Farrar JJ. Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med 2002;347(22):1770-82.

- AAP. Red Book 2015:699.

- Bradley JS, Jackson MA; Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. The use of systemic and topical fluoroquinolones. Pediatrics 2011;128(4): e1034-45.

- Trivedi NA, Shah PC. A meta-analysis comparing the safety and efficacy of azithryomycin over the alternate drugs used for treatment of uncomplicated enteric fever. J Postgrad Med 2012;58(2):112-8.

- AAP. Red Book 2015:698.

- WHO. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of typhoid fever: 22.

- AAP. Red Book 2015: 700.

- Wain et al, Typhoid Fever, Lancet 2015;385(9973):1136-45

- Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Ionnidis JP. Claims for improved survival from systemic corticosteroids in diverse conditions: an umbrella review. Eur J Clin Invest 2012 Mar;42(3):233-44

Editor(s)

- Heather Onyett, MD

Last updated: February, 2023