Vision Screening

Key points

- Untreated eye diseases can result in vision loss. Undiagnosed eye disease and vision loss are more common among new immigrants and refugees from developing countries.1

- Visual acuity is the most important indicator of ocular health. Immigrants and refugees should have visual acuity assessed soon after arrival.1

- 5% to 10% of preschoolers will have undetected visual difficulties which, if left untreated, may interfere with proper visual development.2

- Strabismus (ocular misalignment) and refractive errors are the most common causes of impaired development of vision (amblyopia).

- Some common causes of blindness elsewhere in the world are rarely seen in Canada, such as trachoma (Chlamydia trachomatis) and xerophthalmia (blinding malnutrition).

- Vitamin A supplements prevent xerophthalmia. Infants and children new to Canada, from 6 months to 59 months of age, should be prescribed an age-appropriate daily multivitamin supplement.3

- A careful vision assessment may reveal underlying unrecognized or unacknowledged causes of learning difficulties.

Why vision screening is important

To achieve optimal development, children and youth need to see well. The World Health Organization reports that about 19 million children younger than 15 years of age worldwide are visually impaired. Of these children, 12 million are impaired as a result of refractive errors, a readily treatable condition. Some common causes of blindness in children in other parts of the world are seen only rarely in Canada, such as trachoma (Chlamydia trachomatis) and xerophthalmia (blinding malnutrition).4

Unmasking a developmental delay

An apparently hyperactive 10-year-old boy is brought to your office for assessment. The family moved to Canada from Eastern Europe as refugees, and although they have been in Canada for over six months, they speak little French or English. Their boy was reported to be disruptive in class and was thought to have attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

A routine examination reveals very poor vision in his left eye and moderately impaired vision in his right eye. This spurs a funduscopic examination that reveals severe chorioretinitis. Further questioning of the parents reveals that he had been treated for toxoplasmosis for one month when he was 2 years old.

Follow-up investigations confirm the congenital toxoplasmosis diagnosis and severe developmental delay, even when he is tested in his mother tongue.

Learning points

- Immigrants and refugees should have visual acuity assessed soon after arrival.

- Many newcomers to Canada do not have the English or French language skills to understand and give a thorough history. Interpreters can play a crucial role in aiding communication.

- Visual impairment may mask, be confused with, or co-occur with developmental disabilities. Read more about developmental assessment for newcomer children.

Risk factors associated with impaired vision

- Family history of significant myopia, hyperopia or strabismus, as well as infantile cataracts and infantile glaucoma.

- Genetic diseases, including sickle cell disease, Down syndrome, albinism, phakomatoses and Alport syndrome.

- Medications used during pregnancy, such as streptomycin, gentamycin, quinolone or antivirals.

- Prematurity, including retinopathy of prematurity.

- Congenital anomalies, such as cataracts and microphthalmia.

- Injury, notably from harmful traditional eye medications or cosmetics (e.g., the juice of squeezed plant leaves, lime juice, kerosene, animal or human urine, preparations containing lead).5

- Malnutrition, especially vitamin A deficiency.

- Congenital or acquired infectious diseases, such as rubella, measles, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, trachoma and onchocerciasis.

Trachoma, onchocerciasis and xerophthalmia

Trachoma, onchocerciasis and vitamin A deficiency (causing childhood blindness) affect the poorest of the poor. They are indicators of poverty that particularly affect women and children.6

Trachoma

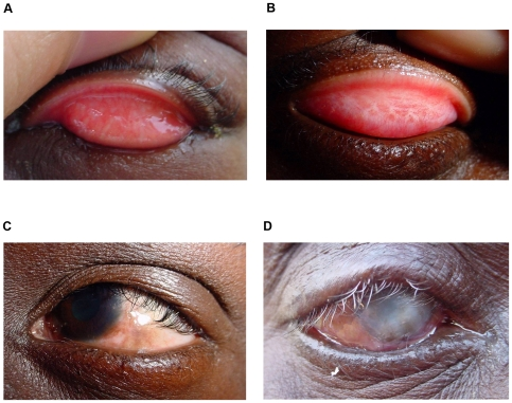

Figure 1: Trachoma

Clinical features of trachoma

- Active trachoma in a child, characterized by a mixed papillary (TI) and follicular response (TF).

- Tarsal conjunctival scarring (TS).

- Entropion and trichiasis (TT).

- Blinding CO with entropion and trichiasis (TT).

Source: Burton MJ, Mabey DC. The global burden of trachoma: A review.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009;3(10):e460. Image accessed from OpeniBeta:

Trachoma (Chlamydia trachomatis) begins slowly, presenting first as “pink eyes”. If left untreated, the infection eventually causes the eyelid to turn inward. The eyelashes rub on the eyeball, resulting in intense pain and scarring of the cornea. This ultimately leads to irreversible blindness, typically between 30 and 40 years of age. Trachoma can be detected using a standard office ophthalmoscope.

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis, or river blindness, is a parasitic disease caused by the filarial worm Onchocerca volvulus. It is transmitted through the bites of infected blackflies of Simulium species.

Onchocerciasis requires a referral to an ophthalmologist or optometrist for a slit-lamp examination of the anterior part of the eye, where the larvae or resulting lesions become visible. Eye lesions occur after years of severe infection and are not usually found in people under age 30.7 More detailed information is available in this resource about onchocerciasis.

The best preventive measures include personal protection against biting insects. A parent handout on insect repellant use in children is available from the Canadian Paediatric Society.

Xerophthalmia

Vitamin A deficiency can lead to scarring of the cornea. This is a major cause of blindness in children in developing countries, known as xerophthalmia (blinding malnutrition). Approximately 127 million preschool-aged children worldwide are vitamin A-deficient, a problem that can be addressed at minimal cost—about 5 cents per dose for a vitamin A supplement.

Vitamin A deficiency can be addressed in young newcomers to Canada through supplementation as well as dietary modifications. The recommended daily intakes of vitamin A for all age groups are available on the Health Canada website.

To help combat xerophthalmia, the CDC recommends an age-appropriate daily multivitamin for all children aged 6 months to 59 months. Specific supplementation may be of benefit in children older than 5 years of age. 3

Screening recommendations

The Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health recommends age-appropriate screening for visual impairment soon after newcomers arrive. Patients should be referred to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for evaluation if presenting vision is <6/12 with the patient’s corrective lenses in place.1

A newcomer child’s eye anatomy and visual function should be checked at regular intervals. Beginning with newborns, assessments should include the red reflex for serious ocular diseases (e.g., retinoblastoma and cataracts), and the corneal light reflex and cover-uncover test and inquiry for strabismus (ocular misalignment).

Subjective visual acuity should be assessed at the preschool stage, usually starting at 3 years of age as well as when there is a complaint. An assessment should also include ocular alignment and ocular media clarity.

Recommendations for when to screen

Because untreated eye diseases can result in vision loss, regular vision screening is recommended by a number of organizations,1,2,8 including the CPS, as follows:

- Age-appropriate testing at health care practitioner visits beginning with newborns and continuing until the age of five.9

- Visual acuity tests with age-appropriate tools.

- For all children, at least one assessment between 3 to 5 years of age (level of evidence rating AII).

- For all immigrants and refugees, testing soon after arrival.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has concluded that no evidence currently exists to sufficiently assess the benefits or harms of vision screening for children younger than 3 years of age. One study has indicated that earlier screening and treatment is associated with improved vision compared with screening children at 37 months of age.10

Barriers influencing eye care

There are reasons newcomers may not seek or receive appropriate vision care, including:1

- Cost (lack of health insurance to cover eye care).

- Stigma associated with wearing glasses, or a desire to adhere to accepted beauty standards.

- Some eye charts may use symbols and pictograms that are culturally specific. This can affect results.

- Lack of awareness among health professionals of the importance of early screening.11

- Other barriers to accessing health care for immigrants and refugees.

What health professionals can do

- Adopt vision screening practices to detect abnormalities as early as possible. It is essential to test children with their own refractive correction in place. If corrective lenses (glasses) are being worn, they should be kept on during testing.

- When choosing a screening tool for a newcomer child, consider whether symbols/pictograms may be too culturally specific to produce valid results.

- Be aware of the barriers that may interfere with eye care. Ask questions to assess obstacles and to help newcomer patients find potential solutions.

- Ask about traditional treatments and cosmetics for the eyes.

- Arrange for an interpreter if language difficulties exist.

Selected resources

- Backman H. Children at risk of developing amblyopia: When to refer for an eye examination. Paediatr Child Health 2004;9(9):635-7.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee. Vision screening in infants, children and youth. Paediatr Child Health 2009;14(4):246-8.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vision Health Initiative(VHI)—Common eye disorders.

- A live interview explaining detection of cataracts with an ophthalmoscope is available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/749652. Note that access requires subscription to Medscape.

References

- Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E824-925.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee. Vision screening in infants, children and youth. Paediatr Child Health 2009;14(4):246-8.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012. Immigrant and refugee health, General refugee health guidelines. See Iron-deficiency anemia (IDA).

- WHO. Visual impairment and blindness. Fact sheet no. 282, June 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infant lead poisoning associated with use of tiro, an eye cosmetic from Nigeria – Boston, Massachusetts, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61(30):574-6.

- IAPB/VISION 2020, The right to sight. Seeing is believing—VISION 2020 Report on World Sight, 2002. http://www.who.int/ncd/vision2020_actionplan

- USAID, Neglected Tropical Diseases(NTD) Program. Onchocerciasis or river blindness.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Vision screening for children 1 to 5 years of age: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics 2011;127(2):340-6.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine and Section on Ophthalmology; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Eye examination in infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics 2003; 111(4 Pt 1):902-7.

- Williams C, Northstone K, Harrad RA, et al. Amblyopia treatment outcomes after screening before or at age 3 years: Follow up from randomised trial. BMJ 2002;324(7353):1549.

- Backman H. Children at risk of developing amblyopia: When to refer for an eye examination. Paediatr Child Health 2004;9(9):635-7.

Other works consulted

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vision Health Initiative(VHI)—Common Eye Disorders.

- Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C. Screening for visual impairment in children ages 1-5 Years: Update for the USPSTF. Pediatrics 2011;127(2):e442-79.

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Health care – Refugees.

- Rourke L, Leduc D, Rourke J. 2011. Rourke Baby Record: Evidence-based infant child health maintenance.

Editor(s)

- Danielle Grenier, MD

- Julie Bailon-Poujol, MD

Last updated: February, 2023