Gastrointestinal parasitic infections in immigrant and refugee children

Key points

- Common infections in refugee populations include Giardia and helminthic (worm) infections, e.g., roundworm (Ascaris), whipworm (Trichuris), hookworm, Strongyloides, and Schistosoma.

- While often asymptomatic or subclinical, these infections can also cause significant morbidity and even death.

- Diagnostic testing for children is recommended if there are clinical concerns for infection (gastrointestinal symptoms, failure to thrive, chronic rashes, anemia, eosinophilia). Stool microscopy for ova and parasites can be insensitive, and thus multiple samples on different days are required. For some infections, serum serology or stool molecular testing are preferred.

- Screening with serological tests for Strongyloides and Schistosoma helminth infections is recommended for newly arrived refugees and immigrants from endemic regions of the world. If positive, treatment is recommended even when children are asymptomatic, since these infections can have long-term and serious health consequences.

Overview

Children are prone to acquiring gastrointestinal parasitic infections due to playing in outdoor environments, close contact with other children, and developmental behaviours that impact hygiene. Newcomer children may be at elevated risk, depending on epidemiology in their country of origin and migration journey, particularly if they had exposures to crowded conditions, poor sanitation, or institutionalization.

Most gastrointestinal parasite infections are asymptomatic in healthy individuals. However, they can cause significant gastrointestinal and extraintestinal morbidity. Chronic worm infections may cause long-term organ damage, life-threatening disease in the context of iatrogenic immunosuppression, or neurodevelopmental sequelae.

This section reviews several common and clinically important parasitic infections using the following structure:

·Protozoa - single-celled parasites

- Helminths - worms, which can be further sub-divided into:

- Roundworms (nematodes)

- Flukes (trematodes)

- Tapeworms (cestodes)

Gastrointestinal protozoan infections

Most gastrointestinal protozoa are spread by fecal-oral transmission, either person-to-person or via contaminated food or water. Symptomatic infections typically present with diarrhea; fever is unusual.

Giardiasis:Giardia is the most common intestinal parasitic infection worldwide (1). Many infections are asymptomatic. Giardia can cause a self-limited acute diarrheal illness, or chronic diarrhea. Associated symptoms may include bloating, nausea, anorexia, abdominal pain, steatorrhea, malabsorption, failure to thrive, or anemia. Symptoms can wax and wane. Fever, bloody diarrhea, extraintestinal manifestations, and eosinophilia are atypical.

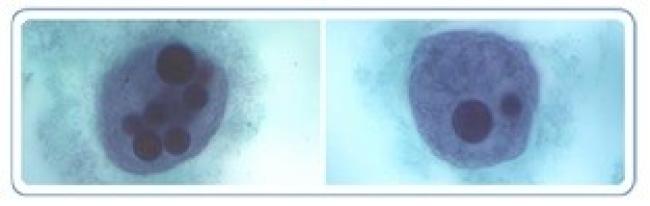

Figure 1. Giardia cyst and trophozoites

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DDx, Giardiasis

Figure 2. Cryptosporidium oocysts

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DDx, Cryptosporidiosis

Figure 3. E. histolytica trophozoites with ingested red blood cells

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DPDx, Amebiasis

Cryptosporidiosis: Cryptosporidium is globally distributed and a leading cause of pediatric diarrheal disease (2). It may be acquired via animal contact (3). Children may be asymptomatic, or present with a self-limited watery diarrhea. Diarrhea may become prolonged, severe, or even fatal in young children or immunocompromised individuals (e.g., HIV/AIDS) (4). Associated features may include fever, vomiting, weight loss, or dehydration, and in immunocompromised people, respiratory or biliary disease. Cryptosporidium infection has been linked to malnutrition, even in the absence of diarrhea (5).

Amoebiasis: Millions of people are infected by Entamoeba histolytica. This parasite causes an estimated 50,000 deaths annually, predominantly in South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Central and South America (6). Most intestinal infections are asymptomatic. However, some progress to abdominal pain, weight loss, watery diarrhea, and/or dysentery (diarrhea with mucous or blood). The course may be acute or chronic, sometimes with alternating diarrhea and constipation, and can mimic inflammatory bowel disease. Rare intestinal complications include gastrointestinal hemorrhage, strictures, necrotizing colitis, and perforation, with risk of death. Extraintestinal disease develops in a small proportion of patients, usually as a liver abscess and occasionally with spread to the pleural space, lungs, pericardium or brain. While rare in children, abscess rupture can be fatal (7). The life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica can be found on the CDC website.

Diagnosis

Stool ova and parasite (O&P) microscopy for identification of trophozoites or cysts is the standard method for diagnosing gastrointestinal protozoan infections. As O&P sensitivity is limited by intermittent shedding of parasites in stool, 2-3 stool samples should be collected on separate days (1). In one study of 1042 international adoptees with (mostly protozoan) gastrointestinal parasites, sensitivity of a single stool O&P was 79%, while 2 and 3 samples increased sensitivity to 92% and 100%, respectively (8).If a specific parasite is suspected based on epidemiology or clinical assessment, the parasite name should be indicated on the requisition, as this may prompt additional specialized testing by the microbiology laboratory.

Stool PCR multiplex assays for protozoa have been developed, with rapid turn-around times and high sensitivity, often superior to stool microscopy (9).

E. histolytica is poorly detected on stool microscopy (sensitivity 25-60%) and is morphologically identical to non-pathogenic commensal Entamoeba species. Stool PCR and antigen detection are preferred (10). E. histolytica serology by enzyme immunoassay can be used as an adjunctive test; it has 95% sensitivity for extraintestinal amebiasis and 70% sensitivity for active gastrointestinal infection, but only 10% sensitivity for asymptomatic colonization and cannot distinguish active from past infection (7). Ultrasound, CT and MRI can identify liver abscesses and other extraintestinal sites of E. histolytica infection.

Treatment

See Table 1 for recommended anti-parasitic treatment for gastrointestinal protozoan infections. Generally, treatment is indicated if symptoms are significant or protracted, or in vulnerable hosts (e.g., immunocompromised). However, E. histolytica infection should always be treated, even in asymptomatic individuals, given the potential for invasive infection and transmission to close contacts (7).

Giardiasis may be recurrent due to drug resistance, re-infection, or host immunodeficiency. Combination drug therapy may be most effective in these cases (11).

Screening for protozoa in asymptomatic newcomers

Stool O&P testing in asymptomatic newcomer children can be considered. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends 2-3 stool O&P tests (with specific testing for Giardia and Cryptosporidium) for migrants from resource-limited settings or low socioeconomic circumstances (12) and for international adoptees (13). 2011 guidelines from the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health do not make this recommendation (14).

Some recommend screening for E. histolytica prior to corticosteroid initiation in individuals with risk factors for colonization, to prevent progression to fulminant colitis (10, 15).

Table 1. Suggested therapy for infections with pathogenic protozoa (16) |

|

Intestinal parasite |

Suggested therapy for children and adolescents |

|

Amoebiasis |

Asymptomatic infection:

If colitis or liver abscess is present: FOLLOWED BY either iodoquinol or paromomycin, as above, to eliminate cysts. |

Cryptosporidiosis

|

Cornerstones of management are supportive care and optimization of immune function. Pharmacologic treatment is generally reserved for immunocompromised hosts or prolonged symptoms.

|

Cyclosporiasis

|

Trimethoprim (TMP)/sulfamethoxazole (SMX): 8-10 mg/kg/day of TMP component PO divided bid x 7-10 days |

|

Giardiasis |

|

Cystoisosporiasis

|

Trimethoprim (TMP)/sulfamethoxazole (SMX): 8-10 mg/kg/day of TMP IV or PO divided bid x 7-10 days |

|

*Metronidazole in liquid form may not be palatable for children. Tablets can be crushed and mixed with semi-solid such as applesauce; consult a pharmacist as needed. ** Nitazoxanide is not licensed in Canada but available through Health Canada’s Special Access Program. It should be taken with food. |

|

Gastrointestinal helminth infections

Millions of people worldwide are infected with gastrointestinal helminths. Transmission occurs via ingestion, skin penetration, or vector inoculation of ova or larvae, and is associated with warm climates, poor sanitation, and poverty. Clinical presentation can vary widely depending on pathogen and host features.

A. Intestinal roundworms (Nematodes)

Figure 4. Ascaris egg and adult female worm

Source: Orange County Public Health

Laboratory, Santa Ana, CA. With permission.

Figure 5. Trichuris (whipworm) egg and adult female worm

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DPDx, Public Health Image Library (PHIL): phil.cdc.gov

Intestinal nematodesare also known as soil-transmitted helminths. The adult worms inhabit the human gastrointestinal tract. The most clinically relevant species are Ascaris lumbricoides (large roundworm), Trichuris trichiura (whipworm), and Ancylostoma and Necator species(hookworms). [Strongyloides stercoralis is addressed in a separate section below.] They are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical areas.

Most pathology associated with these species relates to parasite load, which decreases after a person leaves an endemic area because the adult worms have a relatively short lifespan (months to a few years). People with low parasite loads are usually asymptomatic. With heavier loads, typical symptoms include abdominal pain or distension, nausea, diarrhea, malaise, malabsorption, malnutritionand resultant stunting, and chronic anemia, which in turn may affect a child’s physical and cognitive development. Occasionally, these helminth infections can cause complications requiring surgical intervention (e.g., intestinal or biliary obstruction due to Ascaris, rectal prolapse due to Trichuris).

Diagnosis

At least 2 stool O&P samples collected on different days in preservative should be examined by microscopy (17). Country of origin and any suspicion for specific helminths should be indicated on the requisition. PCR assays for helminths have been developed but are not generally available in Canada.

Treatment

Nematode infections should be treated with anti-helminthics, as outlined in Table 2.

Special mention:Strongyloides stercoralis

Strongyloides stercoralis is a soil-transmitted helminth with unique biology that merits a distinct approach. It is widely endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions. 30-100 million persons worldwide are chronically infected, though this is likely underestimated (18). Strongyloides infection is common in migrants to low-prevalence areas, with overall seroprevalence of 12.2% and highest rates in migrants from the Pacific regions, sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean (19).

The CDC website provides an overview of the life cycle of Strongyloides.Briefly, infective larvae penetrate the skin from contaminated soil, then migrate to the lungs. After ascending the tracheal bronchial tree, larvae are swallowed and mature into adult worms in the small intestine. Ova are produced and shed into the gastrointestinal tract, eventually developing into larvae that return to the soil to complete the life cycle. However, larvae can re-infect the host through the colon or perianal area. This “auto-infection” capacity can lead to a life-long infection, even after migration from endemic areas.

Gastrointestinal features of Strongyloides infection may include non-specific abdominal pain (classically epigastric), heartburn, bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea (possibly alternating with constipation), anorexia, and malabsorption (20).

Strongyloidiasis can affect other systems (20, 21):

- Systemic: Fevers, weight loss, stunted growth in children

- Pulmonary: Transient pneumonitis (Loeffler-like syndrome) during larval migration through the lung (rare)

- Dermatologic: Transient pruritic papules at the site of initial skin penetration; intermittent urticaria; or “larva currens” (pruritic serpiginous erythematous tracks in perianal area, buttocks, and upper thighs).

Most infections with Strongyloides are asymptomatic. Eosinophilia (>500/mL) may be the only abnormality, though is an insensitive marker.

Clinical or subclinical Strongyloides infection can persist for years or decades. The auto-infection cycle may accelerate due to corticosteroids, other immunosuppressive agents, malignancy, or HTLV-1 co-infection. This can lead to a hyperinfection syndrome, with high numbers of larvae migrating through the gut and lungs, with pulmonary infiltrates and respiratory distress. Further progression involves dissemination of adult worms via systemic circulation to other organs, including the brain, liver, heart and skin. Concomitant septicemia or meningitis with enteric Gram-negative bacilli is common, as bacteria exit the gastrointestinal tract alongside the larvae. Hyperinfection and disseminated disease are associated with mortality rates >50% in case series (22).

Figure 6. A hookworm (left), and a Strongyloides (right) filariform infective stage larvae

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Image Library (PHIL),

Dr. Mae Melvin: phil.cdc.gov/phil

Diagnosis

Any immigrant or refugee with exposure to a Strongyloides-endemic area and clinical features of Strongyloidiasis should undergo diagnostic testing. Excretion of Strongyloides larvae in feces is diagnostic but poorly sensitive, requiring numerous samples and specialized concentration techniques (20). Serological tests are preferred due to higher sensitivity (23). Serology has limitations in terms of specificity (cross-reaction with other helminth infections) and sensitivity (decreased in immunocompromised hosts). Stool O&P samples should also be sent in immunosuppressed individuals. In the context of suspected hyperinfection or dissemination, other body fluids should be examined microscopically for O&P (e.g., sputum, cerebrospinal fluid).

Treatment

Consultation with a paediatric infectious diseases or tropical medicine specialist is recommended before commencing treatment.

Ivermectin is the treatment of choice for strongyloidiasis. Treatment with albendazole or thiabendazole is associated with lower cure rates (24), and thus is only recommended if there are contraindications to ivermectin. Combined ivermectin and albendazole therapy is used in hyperinfection and disseminated states (23). The safety of ivermectin has not been formally established for children weighing <15 kg, but retrospective data suggest it is safe and well-tolerated (25). Prior to ivermectin treatment, high burden loa loa co-infection should be excluded in individuals from endemic areas (23).

Prolonged or repeated treatments may be necessary in hyperinfection or disseminated strongyloidiasis, and relapses can occur. In disseminated disease, broad-spectrum antibiotics are indicated for secondary bacterial complications such as sepsis or meningitis.

|

Table 2. Suggested therapies for infections with intestinal roundworms (nematodes) (16) |

|

Intestinal parasite |

Suggested therapy for children and adolescents |

|

Roundworms |

|

|

Pinworms |

|

|

Hookworms |

|

|

Strongyloidiasis |

|

Whipworm

|

|

|

* Not licensed in Canada but available through Health Canada’s Special Access Program. |

|

B. Flukes (Trematodes)

Flukes have a life cycle requiring specific freshwater snails as intermediate host, which determines each species’ geographic distribution. Blood flukes infect humans by penetrating skin surfaces, while food-borne flukes infect humans through the ingestion of certain foods. Due to their tissue-invasive character, all trematodes tend to cause eosinophilia.

Schistosomiasis (“Bilharzia”)

Schistosomiasis is an acute and chronic parasitic disease caused by blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma. There are 6 pathogenic species. Over 250 million people worldwide are believed to be infected with Schistosomiasis. Schistosomiasis is endemic to various tropical and subtropical regions (Figure 7), but >80% of disease occurs in sub-Saharan Africa. Annually, Schistosomiasis is estimated to cause 12,000 deaths (26) and 1.6 million lost disability-adjusted life years (27). Among migrants from endemic areas, a systematic review found Schistosoma seroprevalence of 18.4%, with the highest rates (24.1%) in migrants from sub-Saharan Africa (19).

Figure 7. Geographic distribution of schistosomiasis

Source:Distribution of schistosomiasis, 2003. World Health Organization, 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

More information aboutschistosomiasis can be found on the CDC website. Briefly, people become infected when larval forms of the parasite, released by freshwater snails, penetrate the skin. The larvae enter the bloodstream, and migrate through the lungs to the venous plexuses that drains the intestines (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) or the bladder (S. haematobium). There, they develop into adult worms that live for an average of 3 to 10 years (28). Female worms produce hundreds to thousands of eggs per day. Some eggs pass out of the body in feces or urine, but others become trapped in body tissues such as the intestinal wall, liver, and bladder, causing inflammatory reactions and progressive fibrosis.

Risk of symptoms and complications correlates with intensity of exposure and worm burden. Most children with intestinal schistosomiasis are asymptomatic. If there is intestinal inflammation, children can present with abdominal pain, anorexia, diarrhea (possibly bloody), protein-losing enteropathy, iron deficiency, and/or growth stunting. Liver inflammation can cause hepatomegaly, and if untreated, may progress to periportal fibrosis, portal hypertension, splenomegaly, ascites, and esophageal varices. Hepatocellular function is usually preserved until late-stage disease, with normal bilirubin and liver enzymes (29). It is now recognized that even low worm burdens are associated with anorexia, undernutrition, anemia, and impaired development (30).

- Other manifestations of Schistosomiasis can include: (28, 31)

- Acute schistosomiasis (Katayama disease): Systemic hypersensitivity reaction when the female worm begins to produce eggs, 2 to 12 weeks after exposure. Typically occurs in non-immune individuals (e.g., travelers). Features include fever, malaise, rash, lymphadenopathy, cough, anorexia, abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, tender hepatosplenomegaly and eosinophilia. Resolution usually occurs in 2 to 4 weeks, but fatalities also occur.

- Urogenital: Bladder inflammation most commonly presents as hematuria. Over time, bladder wall fibrosis can lead to urinary reflux, hydronephrosis, recurrent UTIs, nephrotic syndrome, bladder stones, bladder cancer and renal failure. Urogenital schistosomiasis is a risk factor for infertility and HIV infection.

- Dermatologic: At initial larval penetration through the skin, there may be a transient pruritic, papular rash (“cercarial dermatitis”). Chronic urticarial rashes may occur.

- Hematologic: Anemia of chronic inflammation, eosinophilia

- Neurological: Seizures or transverse myelitis (rare)

Diagnosis

Schistosomiasis is definitively diagnosed by detecting eggs in stool or urine specimens by microscopy, though this method has limited sensitivity due to intermittent shedding of eggs, particularly in light infections (28). It is recommended to collect 3 stool specimens (if individual has been exposed to S. mansoni or S. japonicum) and/or 3 urine samples (if exposed to S. haematobium) on 3 separate days. Egg excretion in urine is most likely to be positive at the end of voiding between noon and 3:00 p.m. (31).

Blood serologic tests may be helpful for detecting lighter infections, though they lack sensitivity for some Schistosoma species and have imperfect specificity due to cross-reaction with other helminths. They also cannot distinguish active from past infections. Antigen detection and PCR-based testing in urine and blood have been developed, but these tests are not routinely available in Canada.

- Once Schistosoma infection is diagnosed, the patient should undergo assessment for evidence of disease (32). This includes liver ultrasound to look for portal fibrosis and hypertension, and additionally urinalysis and ultrasound of the urinary tract in migrants from sub-Saharan Africa or the Middle East who were potentially exposed to S. hematobium. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the central nervous system should be ordered for suspected neuroschistosomiasis.

Treatment

Consultation with a paediatric infectious diseases or tropical medicine specialist is recommended.

Praziquantel, which paralyzes and kills the worms within a few hours, is the recommended treatment. Adverse effects are usually mild (transient nausea or malaise). In heavy infections, treatment may result in transient bloody diarrhea or hypotension (29).Praziquantel is effective in >90% of cases, but heavy infections may require repeated treatment. The safety of praziquantel in children <5 years old is not established, but newer data suggest it is safe and well-tolerated (33).

When treating neuroschistosomiasis, praziquantel should be combined with corticosteroids and (possibly) anticonvulsants, to avoid acute exacerbations after the death of ectopic worms (31).

See Table 3 for information on treatment. Note that infections with Schistosoma japonicum or mekongi require higher doses of praziquantel.

Food-borne flukes

Annually, food-borne flukes are estimated to cause over 200,000 illnesses, 7000 deaths, and more than 2 million disability-adjusted life years globally (34). Southeast Asia and South America are the most affected areas.

Figure 8. Trematode eggs found in stool specimens of man |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Image Library |

|

Table 3. Suggested therapy for infections with flukes (trematodes) (16) |

|

Intestinal parasite |

Suggested therapy for children and adolescents |

|

Flukes |

|

|

Sheep liver fluke |

|

Lung fluke

|

|

|

Schistosomiasis (Bilharziasis) |

|

|

* Not licensed in Canada but available through Health Canada’s Special Access Program. |

|

The most important food-borne flukes (or trematodes) infecting humans are the biliary liver flukes (Opisthorchis, Clonorchis, Fasciola hepatica), intestinal flukes (Fasciolopsis buskii) and lung flukes (Paragonimus spp.). These organisms tend to chronically infect specific populations, depending on dietary consumption of certain types of raw fish (Clonorchis, Opisthorchis), crustaceans (Paragonimus) or aquatic plants (F. hepatica, F. buskii) contaminated with the infective stages. Infections may be asymptomatic, or present acutely or chronically with abdominal pain, cough, anorexia, weight loss, urticaria, anemia, and/or eosinophilia. Long-term, Opisthorchis spp. and Clonorchis are associated with liver fibrosis and development of cholangiocarcinoma (29).

The mainstay of diagnosis is stool O&P. Other tests include serological assays, imaging, O&P on sputum or biopsies, or visualizing adult worms during procedures. Treatments are listed in Table 3.

C. Tapeworms (cestodes)

The fish tapeworm Diphyllobothrium latum can be acquired from undercooked fish with encysted larvae. The dwarf tapeworm Hymenolepsis nana is spread between humans. Beef (Taenia saginata) and pork (Taenia solium) tapeworm infections are reviewed elsewhere on this site (Cysticercosis and Taeniasis).

Most infections are asymptomatic, but heavy infections may be associated with abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, fatigue, anemia, or eosinophilia. D. latum can present with vitamin B12 and folate deficiency (35). Hymenolepsis nana may present with anal pruritic mimicking pinworm infection (36). Multiple stool samples should be examined microscopically for ova or proglottids. See Table 4 for information on treatment.

Table 4. Suggested therapy for infections with tapeworms (cestodes) (16) |

|

Intestinal parasite |

Suggested therapy for children and adolescents |

|

Tapeworms |

|

H. nana (dwarf tapeworm) |

|

|

Cysticercosis – See also Cysticercosis and Taeniasis |

|

|

Hydatid cyst (Echinococcus spp) |

|

|

*See reference 22. Niclosamide (manufactured by Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Finland) is not licensed in Canada. Health Canada’s Special Access Program assesses each request. |

|

Screening for helminths in asymptomatic newcomers

Screening for Strongyloides and Schistosoma infections in asymptomatic newcomers from endemic regions may be of value, given the chronic nature and significant health risks of these infections. Treatment of subclinical Strongyloides infection can prevent development of chronic symptoms and disseminated disease. Schistosomiasis is most effectively treated in its early stages, when pathology is inflammatory; advanced liver fibrosis or severe nephropathy may be irreversible (28).

TheCanadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Healthrecommends Strongyloides serology for all newly arrived refugees from South Asia and Africa, and Schistosoma serology for refugees from Africa (i.e., highest risk populations) (37). Other experts recommend Strongyloides and Schistosoma serology for all newcomers from endemic areas (23, 32).Anyone with potential exposure to Strongyloides, even remotely, should be screened before starting immunosuppressive therapy. Unexplained eosinophilia (>500/mL) in a newcomer should prompt testing for Strongyloides, Schistosoma, and/or other helminths, guided by exposure history (17).

Conclusion

Appropriate screening and the early diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal parasites in young newcomers to Canada can help reduce morbidity and prevent complications. Consultation with a paediatric infectious diseases or tropical medicine specialist can be helpful for guiding microbiological testing; applying for restricted antiparasitic drugs through Health Canada’s Special Access Program; prescribing antiparasitic drugs in different age groups and in individuals who may be coinfected with multiple parasites; and monitoring for adverse events.

Acknowledgement

The Canadian Paediatric Society thanks Dr. Laura Erdman of McMaster University for her thorough review and revision of this document.

Selected resources

- Palazzi, DL, ed. 2025 Nelson’s Pediatric Antimicrobial Therapy, 31st ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2025.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.)

- World Health Organization

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Giardia duodenalis infections. In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al, editors. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. p. 390–393.

- Mmbaga BT, Houpt ER.Cryptosporidium and Giardia Infections in Children: a review.Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Aug;64(4):837–850. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2017.03.014.

- Helmy, Y.A.; Hafez, H.M. Cryptosporidiosis: from prevention to treatment, a narrative review. Microorganisms. 2022;10:2456.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Cryptosporidiosis. In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al, editors. Red Book: 2024–2027 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. p. 338–340.

- White, AC. Cryptosporidiosis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 9th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2020. p. 3410–3420.

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al.Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet.2012;380(9859):2095–2128.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Amebiasis. In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al, editors. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Elk Grove Village(IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. p. 225–228.

- Staat MA, Rice M, Donauer S, et al. Intestinal parasite screening in internationally adopted children: importance of multiple stool specimens. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e613–e622.

- Verweij JJ, Stensvold RC. Molecular testing for clinical diagnosis and epidemiological investigations of intestinal parasitic infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014 Apr;27(2):371–418.

- Petri WA, Haque R, Moonah SN. Entamoeba species, including amebic colitis and liver abscess. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2020. p. 3273–3286.

- Mørch K, Hanevik K. Giardiasis treatment: an update with a focus on refractory disease. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020 Oct;33(5):355–364.

- Meneses C, Chilton L, Duffee J. Immigrant Health Toolkit. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; [cited 2025 Jun 20].

- Jones VF, Schulte EE, AAP Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care. Comprehensive health evaluation of the newly adopted Child. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20190657.

- Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011 Sep 6;183(12):E824–E925. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313.

- Shirley DT, Farr L, Watanabe K, et al. A review of the global burden, new diagnostics, and current therapeutics for amebiasis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018 Jul 5;5(7):ofy161.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Drugs for parasitic infections. In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al, editors. Red Book: 2024–2027 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. p. 1068–1112.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). Intestinal Parasites. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [cited 2025 Jun 2].

- Buonfrate D, et al. The global prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Pathogens. 2020 Jun 13;9(6):468.

- Asundi A, et al. Prevalence of strongyloidiasis and schistosomiasis among migrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019 Feb;7(2):e236–e248.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Strongyloidiasis (Strongyloides stercoralis). In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al, editors. Red Book: 2024–2027 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. p. 822–825.

- Tamarozzi F, MartelloE, Giorli G, et al. Morbidity associated with chronic Strongyloides stercoralis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019 Jun;100(6):1305–1311.

- Geri G, Rabbat A, Mayaux J, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome: a case series and a review of the literature. Infection. 2015;43:691–698.

- Boggild AK, Libman M, Greenaway C, et al. CATMAT statement on disseminated strongyloidiasis: prevention, assessment and management guidelines. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2016 Jan 7;42(1):12–19.

- SuputtamongkolY, Premasathian N, Bhumimuang K, et al. Efficacy and safety of single and double doses of ivermectin versus 7-day high dose albendazole for chronic strongyloidiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011 May 10;5(5):e1044.

- Jittamala P, Monteiro W, Smit MR, et al. A systematic review and an individual patient data meta-analysis of ivermectin use in children weighing less than fifteen kilograms: Is it time to reconsider the current contraindication? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021 Mar 17;15(3):e0009144.

- World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis. Geneva: WHO; [cited 2025 May 5].

- Montresor A, Mwinzi P, Mupfasoni D, Garba A. Reduction in DALYs lost due to soil-transmitted helminthiases and schistosomiasis from 2000 to 2019 is parallel to the increase in coverage of the global control programmes. 2022. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(7):e0010575.

- McManus DP, Dunne DW, Sacko M, et al. Schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 Aug 9;4(1):13.

- Maguire, JH. Trematodes (Schistosomes and Liver, Intestinal, and Lung Flukes).In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 9th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2020. p. 3451–3462.

- King CH, Dickman K, Tisch DJ. Reassessment of the cost of chronic helmintic infection: a meta-analysis of disability-related outcomes in endemic schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1561–1569.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Schistosomiasis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, editors. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases 33rd ed. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. p. 753–756.

- Makhani L, Kopalakrishnan S, Bhasker S, et al. Five key points about intestinal schistosomiasis for the migrant health practitioner. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021 Mar–Apr;40:101971.

- Mutapi F, Rujeni N, Bourke C, Mitchell K, Appleby L, et al. (2011) Schistosoma haematobium Treatment in 1–5 Year Old Children: Safety and Efficacy of the Antihelminthic Drug Praziquantel. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(5):e1143.

- World Health Organization. 2015. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015. Geneva: WHO; 2015 [cited 2025 Jun 3].

- Fairley JK, King CH. Tapeworms (Cestodes). In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2020. p. 3463–3472.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Other tapeworm infections. In: Kimberlin DW, Banerjee R, Barnett ED, et al, editors. Red Book: 2024–2027 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Elk Grove Village (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024. p. 845–848.

- Khan K, Heidebrecht C, Sears J, et al. Appendix 8: Intestinal parasites – Strongyloides and Schistosoma: evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. In: Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E824–E925. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090313.

Reviewer(s)

Laura Edrman, MD

Last updated: October, 2025