Substance Use and Immigrant Youth

Key points

- Statistically, substance use disorders are less common in immigrant youth than in their Canadian-born peers.

- The risk of developing a substance use disorder seems to increase with time spent in Canada and level of acculturation.

- Being able to communicate openly with family about new life stressors can be an important protective factor for substance use, while not having this support is a key risk factor. This is true for newcomer and Canadian-born youth.

- Identifying comorbid psychiatric conditions is an important part of substance use assessment for any patient.

- Useful treatment strategies include psychoeducation that involves other family members and motivational interviewing.

Epidemiology

Data on substance use among young newcomers to Canada are limited. Substance use in first-generation youth new to Canada has been reported to be significantly lower than second-generation youth, who report less use than third and later generations.1

A U.S. study also found that substance use disorders are less common in first- and second-generation immigrant youth than in third or later generations. The same study found that substance abuse was lowest in recently arrived immigrants (i.e., settled ≤4 years).2

Overall, research supports the so-called immigrant paradox, where first-generation immigrants show better outcomes in terms of education, behaviour and health – including lower levels of substance abuse – than the native-born population.3

A number of factors influence substance use behaviour among immigrant youth.3 For example, youth from cultures that strictly prohibit substance use and strongly adhere to familial authority are less likely to abuse substances in Canada than youth from countries where substance abuse is endemic.4,5

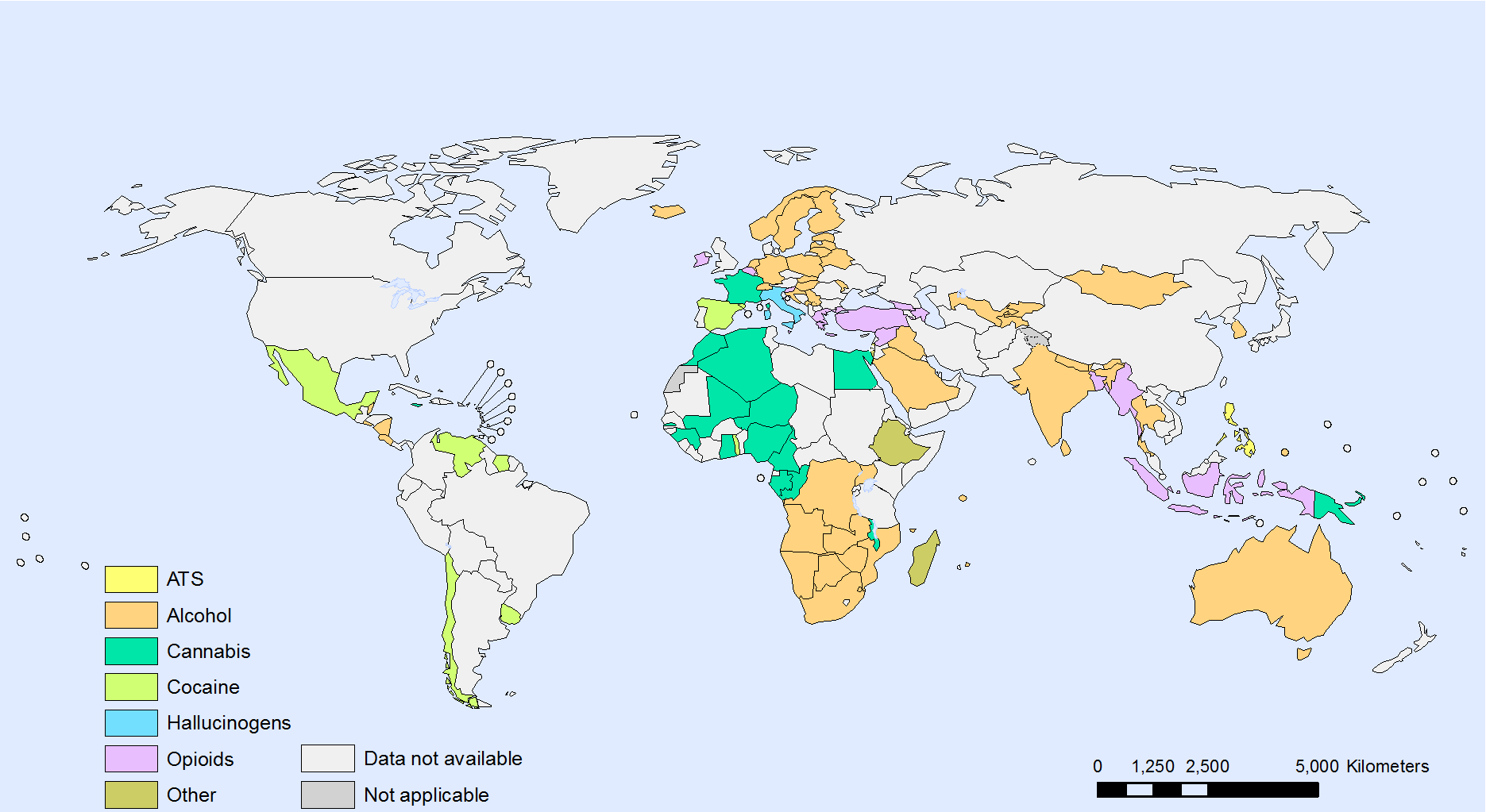

The WHO has an interactive resource that includes statistics for substance abuse around the world.

Figure 1. Main psychoactive substance for treatment entry worldwide (2008)

Source: Reproduced, with the permission of the publisher, from Interactive charts: Substance abuse. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2012 (Main psychoactive substance for treatment entry worldwide, 2008 http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/substance_abuse/treatment_alcohol_drugs/atlas.html, accessed 4 February 2014)

Young newcomers may already have been exposed to or used substances that are uncommon in Canada, such as khat, which is used in parts of Africa (notably in Somalia) and the Middle East.6 Cultural background shapes attitudes to substance use and misuse.7 For example, Indian cultures have a long historical tradition of using of plant products, which, combined with caste, religion and local customs, influence contemporary drug use. However, it is also important for clinicians not to make assumptions based on a youth’s country of origin (see Cultural Competence).

Canadian data indicate that:

Alcohol is the most common substance used by Canadian youth, followed by cannabis and cigarette smoking. Cannabis is the most common substance of daily use.8

Less commonly used substances include hallucinogenic drugs (e.g., psilocybin [magic mushrooms], mescaline), ecstasy, cocaine, methamphetamine and OxyContin.8

The occurrence of substance use among youth in Canada varies by region.9

Risk and protective factors for immigrant youth

A number of risk and protective factors for substance use are especially relevant for immigrant youth:10-12

Risk factors

- Experiencing discrimination

- Acculturation (see also “Specific considerations” below) and the number of years in the ‘new’ country

- Ethnic dislocation (i.e., a lack of integration into either the youth’s original or adopted culture). Dislocation is also influenced by disparities between a family’s culture of origin and their current community, where they might feel out of touch with both cultures.

- Disruption of traditional family hierarchies, while transitioning to Western culture. For example, parents may depend heavily on their children for community access or interaction, which can upset parent–child dynamics.

Protective factors

- Religious beliefs

- Ethnic pride

- Being less acculturated

- Cultural norms that emphasize abstinence or minimal drinking

- Strong parental and family influences

- Staying in school

- Certain genetic characteristics (e.g., an inactive ALDH2-2 gene in Asians, which may help protect against heavy drinking)

Specific considerations for young immigrants

- The risk for substance abuse among first-generation immigrant youth is lower than for second- and third-generation youth.1

- Immigrant youth are more likely than their native-born peers to be socially disadvantaged or experience poverty.13,14

- A youth’s ability to communicate openly with family about life stressors may be an important protective factor for substance use, while lack of access to family support may be a key risk factor.15

- Practitioners should take time to identify protective factors in newcomer patients and families. They may be able to draw on these factors to prevent substance misuse.

- Risk factors for the development of substance use disorders among immigrant youth appear to increase with time since immigration and greater acculturation.11

- Among first-generation immigrant youth, those who are more acculturated may be less able to resist peer pressure to use substances.16

- Acculturation in immigrant children and youth is a complex phenomenon. Traditional one-dimensional models of acculturation (i.e., “less” to “more” acculturated) are inadequate, and recent literature describes a multidimensional process. (see Adaptation and Acculturation)

The protective effect of recent immigration on substance use may diminish more quickly for alcohol than for tobacco or cannabis. In the U.S., alcohol use by immigrant youth has been reported to increase to levels equal to their U.S.-born peers after only 4 years, particularly in young men.2

Treatment barriers

Young immigrants can encounter a number of barriers when seeking or accessing care for substance abuse:17

- Family resistance to a mental illness diagnosis, including addiction, due to cultural stigmatization or feelings of shame.18

- Under-recognition of addiction problem. Individuals from certain cultures are more likely to ‘somatise’ symptoms as a result of substance use (i.e., report them as physical symptoms).17

- Language and cultural barriers affecting communication.18

- Distrust of and unfamiliarity with Western medical practices, including addiction treatment strategies. Approaches to treatment in their native country (e.g., long-term institutionalization) may increase fear and prejudice.

- Lack of awareness that care is available.

- Lack of culturally competent services (i.e., tailored to language, cultural beliefs and values).

Young immigrants seeking help for addiction face many of the same barriers encountered by other newcomers navigating the Canadian health care system. These are addressed in detail on the following pages Barriers and Facilitators to Health Care for Newcomers, Using Interpreters in Health Care Settings and Mental Health Promotion.

Screening and assessment

Identifying patients who require specialized care for substance abuse is important for ensuring early intervention. Clinicians may want to use CRAFFT, a six-question substance-use screening tool validated for use in adolescents. The CRAFFT tool should not be used in isolation but as one part of a broad, confidential and developmentally appropriate adolescent psychosocial assessment. Identifying comorbid psychiatric conditions is another important aspect of assessing a substance use disorder.

Diagnosis

Substance use can range from the recreational, which may have negligible health or social implications, to habitual dependence. The DSM-5 (2013), uses the term substance use disorder, which can be mild, moderate or severe. (see Table 1)

Although the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for other substances (e.g., cannabis, hallucinogens) are similar, please consult the DSM-5 for the full criteria.19

|

Alcohol use disorder |

|---|

|

|

Source: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn., 2013, DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

Clinicians may want to take the following factors specific to adolescents into account,20

- Comorbid psychiatric disorders are often present in adolescents with a substance use disorder. Clinicians should screen for the presence of comorbidity. The most common psychiatric comorbidities are:

- conduct disorder,

- attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and

- oppositional defiant disorder.

These conditions are usually primary to the substance use disorder. Two other common comorbities, anxiety and mood disorders, are often secondary to the substance use disorder.21 Use of cannabis or other substances can also contribute to the onset or exacerbation of primary psychotic disorders.19 The factors specific to adolescents that clinicians need to be aware of include the following:

- Academic problems, truancy, breaking curfew or lying to parents.

- Adolescents may not show symptoms of alcohol withdrawal because of a shorter history of use compare with adults.

- Adolescents tend to binge drink and do not usually drink every day. Information on binge drinking in adolescence, including information for parents, is available from the Canadian Public Health Association.

- Adolescents may be misusing several substances at the same time (e.g., alcohol and cannabis). Adults tend to misuse a single substance.

- Adolescents are more likely to show comorbid behavioural problems. Adults are more likely to develop a mood or anxiety disorder.

Treatment

Treatment approaches for substance use disorders in youth are somewhat different than for adults: the role of family is central, and issues around capacity, consent and confidentiality are typically encountered.

Clinicians should become familiar with community resources and local specialists in adolescent concurrent disorders, particularly when they are culturally competent or focused on care for immigrant youth. Information on treatment services in Canada is available on the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse website. Readers may also wish to refer to the Cultural Competence section in this resource.

Further guidance specific to adolescents can be found here:

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee. Harm reduction: An approach to reducing risky health behaviours in adolescents.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Substance Abuse. Tobacco, Alcohol, and Other Drugs: The Role of the Pediatrician in Prevention, Identification, and Management of Substance Abuse.

Regardless of treatment choice, it is difficult to embark on an effective treatment plan without engaging the family in communication and support. If an interpreter is needed, then using an objective third party who is not a relative becomes essential. Youth should not be used to translate for family members. Information about using interpreters is available elsewhere in this resource.24,25

Prevention

Research has emphasized that the low risk of substance use in recently arrived immigrant youth (<4 years in Canada) is an important lever for health care providers working to prevent or delay substance use.2,22 Interventions that promote positive youth development and address common risk and protective factors have been shown to reduce multiple adolescent risk behaviours, including substance use.23

Prevention programs and policies tailored to immigrant youth remain a health care gap in Canada. There are examples of national preventive programs that target youth generally:

- A Drug Prevention Strategy for Canada's Youth, led by the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

- The Federal government’s National Anti-Drug Strategy.

Selected resources

- Bukstein OG, Bernet W, Arnold V, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005;44(6):609-21.

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Substance abuse in Canada: Youth in focus.

- Kelty Mental Health Resource Centre. Families, together: Supporting the mental well-being of children and youth

- Kids Help Phone. Alcohol and drugs.

- Kulig JW; American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Substance Abuse. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs: the role of the pediatrician in prevention, identification, and management of substance abuse. Pediatrics 2005;115(3):816-21.

- Leslie KM; Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee. Harm reduction: An approach to reducing risky health behaviours in adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 2008;13(1):53-6.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Issue: Diversity.

- Veldhuizen S, Urbanoski K, Cairney J. Geographical variation in the prevalence of problematic substance use in Canada. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52(7):426-33.

References

- Hamilton HA, Noh S, Adlaf EM. Adolescent risk behaviours and psychological distress across immigrant generations. Can J Public Health 2009;100(3):221-5.

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Matsumoto A, et al. Substance use, generation and time in the United States: The modifying role of gender for immigrant urban adolescents. Soc Sci Med 2012;75(12):2069-75.

- Bui HN. Racial and ethnic differences in the immigrant paradox in substance use. J Immigr Minor Health 2013;15(5):866-81.

- Guarino H, Moore SK, Marsch LA, Florio S. The social production of substance abuse and HIV/HCV risk: an exploratory study of opioid using immigrants from the former Soviet Union living in New York City. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2012;12:2.

- Jaffe JH. Commonalities and diversity among drug-use patterns in different countries. In: Edwards G, Arif A, eds. Drug problems in the sociocultural context: A basis for policies and programme planning. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1980.

- Tulloch AD, Frayn E, Craig TK, et al. Khat use among Somali mental health service users in South London. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012;47(10):1649-56.

- Sharma HK. Sociocultural perspective of substance use in India. Subst Use Misuse 1996;31(11-12):1689-714.

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Substance Abuse in Canada: Youth in Focus. Ottawa, Canada; CCSA 2007.

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Cross-Canada Report on Student Alcohol and Drug Use.

- Badr LK, Taha A, Dee V. Substance abuse in Middle Eastern adolescents living in two different countries: Spiritual, cultural, family and personal factors. J Relig Health 2013; DOI:10.1007/s10943-013-9694-1.

- Di Cosmo C, Milfont TL, Robinson E, et al. Immigrant status and acculturation influence substance use among New Zealand youth. Aust N Z J Public Health 2011;35(5):434-41.

- Horigian VE, Lage OG, Szapocznik J. Cultural differences in adolescent drug abuse. Adolesc Med Clin 2006;17(2):469-98.

- Georgiades K, Boyle MH, Duku E. Contextual influences on children’s mental health and school performance: The moderating effect of family immigrant status. Child Dev 2007;78(5): 1572-91.

- Beiser M, Hou F, Hyman I, Tousignant M. Poverty, family process, and the mental health of immigrant children in Canada. Am J Public Health 2002;92(2):220-7.

- Prado G, Huang S, Schwartz SJ, et al. What Accounts for differences in substance use among U.S.-born and immigrant Hispanic adolescents? Results from a longitudinal prospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health 2009;45(2):118-25.

- Wall JA, Power TG, Arbona C. Susceptibility to antisocial peer pressure and its relation to acculturation in Mexican-American adolescents. J Adolescent Res 1993;8(4):403-18.

- Fong TW, Tsuang J. Asian-Americans, addictions, and barriers to treatment. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4(11):51-9.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 2009. Improving mental health services for immigrant, refugee, ethno-cultural and racialized groups: Issues and options for service improvement.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn., 2013, DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- Weis R. Substance use disorders in adolescents. In: Introduction to Abnormal Child and Adolescent Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2008.

- Milin R, Walker S. Life cycle: Adolescent substance abuse. In: Ruiz P, Strain E (eds). Lowinson and Ruiz's Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook, 5th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

- Blake SM, Ledsky R, Goodenow C, et al. Recency of immigration, substance use, and sexual behavior among Massachusetts adolescents. Am J Public Health 2001;91(5):794-8.

- Catalano RF, Fagan AA, Gavin LE, et al. Worldwide application of prevention science in adolescent health. Lancet 2012;379(9826):1653-64.

- Leanza, Y., Miklavcic, A., Boivin, I., & Rosenberg, E. Working with interpreters. In Cultural consultation: Encountering the Other in Mental Health Care. Springer 2014;89-114.

- Leng, J. C., Changrani, J., Tseng, C.-H., & Gany, F. Detection of depression with different interpreting methods among Chinese and Latino primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2010;12(2):234-241.

Reviewer(s)

- Daphne Korczak, MD

- Rachel Kronick, MD

Last updated: November, 2021