HIV/Aids in Children and Youth

Key points

- Immigrant and refugee children arriving in Canada are at increased risk for HIV infection compared with Canadian-born children.

- Estimates of HIV prevalence by country are readily available,1 and can be used to support decisions about HIV testing in children.

- HIV testing should be carried out in children born to a woman living with HIV, children with other risk factors for HIV acquisition, or children with clinical manifestations consistent with HIV.

- Pre- and post-test counselling should be provided in all cases, both to parent(s) or guardian(s) and the child, as appropriate for age.

- Children who test positive for HIV should be referred to a multidisciplinary health care team with expertise in paediatric HIV care.

Background and rationale

HIV is a retrovirus capable of affecting several cells of the immune system, causing dysfunction and increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections. Most notably, the virus enters CD4+ T lymphocytes, replicating within and ultimately leading to their depletion. The CD4 cell count is therefore an indicator of the extent of immunodeficiency in an HIV patient. The lower the CD4 count, the wider the range of opportunistic infections a patient is at risk for. Left clinically untreated, HIV infection will eventually lead to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and death.

HIV infection can be acquired by children in a few different ways:

Routes of HIV transmission in children and youth

- Mother-to-child transmission

- Perinatal

- Breastfeeding*

- Feeding of premasticated food*

- Sexual contact

- Consensual sex (adolescents)

- Sexual assault

- Health care-associated

- Blood transfusion

- Reused needles and syringes

- Traditional practices

- Circumcision

- Scarification

* A surrogate or other caregiver could also be the source of transmission.

- Mother-to-child transmission may occur through intrauterine or intrapartum (perinatal) exposure, or via breastfeeding after birth. Undisclosed breastfeeding or undocumented surrogate feeding should be considered as possible causes when a child has an unexpected diagnosis of HIV.

- Transmission is also possible via feeding of premasticated food from the mother or other caregiver to an older baby or toddler, through blood in saliva.

- Transfusion of blood products was once a prominent route of HIV acquisition in Canada. Every donation to Canadian Blood Services is now tested for HIV, and the risk of transmission by this route is estimated to be less than one in 8 to 12 million.2 However, infection due to a blood product transfusion may be a consideration in children from other parts of the world, where screening of donors and blood products is less rigorous.

- Unprotected sex and injection drug use are prominent routes of transmission among adolescents and young adults. Sexual assault should be considered when an unexpected infection occurs in a child of any age.

- The reuse of medical equipment, such as syringes and needles, has been implicated as a source of HIV infection in some low-resource countries.

- Rarely, transmission may occur through use of contaminated equipment for traditional circumcision or cultural practices, such as scarification.3

The prognosis of perinatally acquired HIV was once very poor, and death during childhood was the norm. High mortality relates to differences in how infants and young children handle primary HIV infection when compared with adults. In general, HIV viral loads remain higher for longer periods in young children, hastening the development of immune deficiency and shortening time to development of an AIDS-defining illness. Without treatment, 1 in 5 perinatally infected children will develop AIDS in the first year of life, with a median age for AIDS diagnosis at around 5 years. Fortunately, this prognosis has changed markedly in Canada and other settings where HIV treatment programs for children are in place.4,5

With the availability of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), survival into adulthood in good physical health has become the expectation. It is therefore very important to diagnose HIV as early as possible, so that optimal management – including cART when indicated – can be initiated. Provision of cART is also an effective public health intervention for adolescents and adults because it prevents transmission to discordant sexual contacts6 and from mother to child.7,8 Primary care providers are usually the first health professionals to encounter immigrant and refugee children, providing a unique opportunity to initiate health screening. The following recommendations are intended to support practice with advice about HIV testing in children and youth and procedures for early referral of patients found to be HIV-infected.

Epidemiology and burden

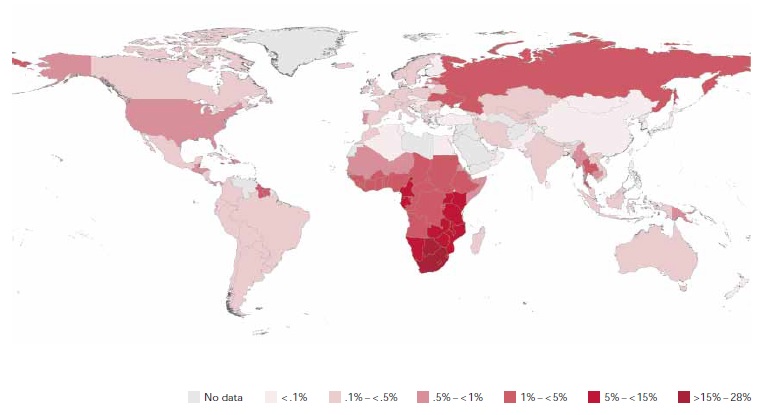

In 2011, an estimated 3.3 million children aged 0 to 14 years were living with HIV worldwide. However, there have been some encouraging trends in recent years. Although an estimated 330,000 new infections occurred in 2011, incidence among children is decreasing substantially as programs to prevent mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV expand. AIDS-related mortality is also declining, as cART becomes increasingly available for children in resource-poor countries. Table 1 provides a summary of UNAIDS prevalence estimates for HIV by region, in 2010. Ranges of prevalence by country are shown in Figure 1. The majority of HIV-infected children (3.1 million) are living in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa.1

| Region | Estimated prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 4.9 |

| Middle East / Northern Africa | 0.2 |

| South and southeast Asia | 0.3 |

| East Asia | 0.1 |

| Oceania | 0.3 |

| Latin America | 0.4 |

| Caribbean | 1.0 |

| Eastern Europe / Central Asia | 1.0 |

| Western and central Europe | 0.2 |

| North America | 0.6 |

| Source: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), World Aids Day Report, 2011:10-11. | |

Figure 1: Global prevalence of HIV, 2009

Source: UNAIDS/ONUSIDA Report on the Global Aids Epidemic, 2010, with permission.

In Canada, the vast majority of HIV-infected children aged 0 to 14 years acquired the virus perinatally. Between 2002 and 2005, 89% of immigrant and refugee children identified as HIV-positive after arrival were of African origin. Most of these children were perinatally infected according to history, and only 11% were on some form of antiretroviral therapy at the time of their positive test in Canada.9

Screening

Pre-departure process

HIV testing has been included in the Citizen and Immigration Canada (CIC) Immigration Medical Examination for applicants aged 15 years and older since 2002. While HIV status is taken into account when considering acceptance of an immigrant’s application, based on health care utilization estimates, a positive HIV test cannot be used as a criterion for excluding refugees and refugee claimants, according to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act.10 HIV-positive applicants admitted to Canada should receive information from the visa or immigration office containing contact information and telephone numbers for public health and HIV services in their province or territory of destination.11 Refugees who are not government-assisted (e.g., privately-sponsored refugees, refugee claimants) may not have received pre-departure screening.

Upon arrival, regional public health authorities should be notified by CIC of immigrants or refugees who have tested positive for HIV, which should lead to arrangements for confirmatory testing in Canada. There is currently no mechanism in place to ensure the patient is subsequently engaged in care. Children aged 0 to 14 years are rarely screened for HIV before arriving in Canada, and may not have been tested even if their mother was known to be infected.

Recommendations for post-arrival testing

The Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH) recommends HIV screening for adolescents and adults from countries with an estimated HIV seroprevalence greater than 1%.12 Estimates of HIV prevalence by region and country are available at the UNAIDS website. Sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and the Eastern Europe/Central Asia region have HIV prevalence estimates greater than 1% (Table 1). It should be noted that although several regions have an overall prevalence of less than 1%, some countries and populations within a particular region may exceed that benchmark. Immigrants and refugees may also be coming from countries where HIV incidence is increasing over time, or from areas of conflict with high rates of transmission due to sexual violence. HIV testing should be considered in these scenarios as well.

The decision to test a child for HIV is made by the clinician, on an individual basis. Currently, testing is recommended for children younger than 15 years of age when the ‘principal applicant’ has been found to be HIV-infected.12 HIV testing should also be done if the child’s birth mother is deceased and the cause of death is suspected to be AIDS-related. If the child has arrived with a female guardian, providers should clarify whether that person is the birth mother. If the birth mother has not accompanied the child to Canada, testing is reasonable if the HIV prevalence is greater than 1% in the patient’s country of origin. Testing is also recommended if there is a risk factor for transmission other than mother-to-child acquisition, such as suspected or known sexual abuse, or a blood product transfusion in the country of origin. If there is a significant risk factor, testing should be carried out regardless of reported or documented results from the country of origin.

Some experts recommend testing all children from countries in which the HIV prevalence is greater than 1%, although this is not routine practice for screening immigrants and refugees in all centres. Testing should be carried out for these children – regardless of age – unless all of the following criteria are met: the birth mother is present and known to be HIV negative through appropriate testing; there are no risk factors for HIV acquisition in the child’s history; and the child has no clinical manifestations consistent with HIV/AIDS.

Paediatricians and other providers caring for adolescents aged 15 years and older should consider HIV in these patients if there is a risk factor or consistent clinical finding. These individuals are entering the age range at highest risk for acquiring a new infection.1 Testing may not always have been done, especially among refugees who are not government-assisted. Furthermore, the results of testing may not always be available, and even in the context of a documented negative result, a patient may have been in the so-called ‘window period’ for developing HIV antibodies. A false negative test can occur if the infection was recently acquired, typically within the preceding 2 to 4 weeks. Failure to perceive risk in this age category has been associated with delayed diagnosis.13

When to test for HIV among immigrant and refugee children

- Parent tested positive for HIV (pre-departure or post-arrival)

- Birth mother deceased due to known (or suspected) AIDS-related illness

- Birth mother not in Canada and child is from a region or country with > 1% HIV prevalence*

- Child or adolescent has a risk factor for transmission

- Adolescent is from a region or country with > 1% HIV prevalence or is found to be pregnant

- Child or adolescent has clinical manifestations consistent with HIV infection

* Some experts recommend HIV testing of all children aged < 15 years if they are from a region or country with > 1% prevalence.

Naturally, there are a number of clinical scenarios that should prompt consideration of HIV and appropriate testing. Various symptoms, physical findings, and diagnoses often associated with an underlying HIV infection are summarized below. HIV testing should be performed for patients diagnosed with opportunistic infections, such as pneumocystis (PCP) pneumonia, cryptococcal meningitis, toxoplasmosis of the central nervous system, cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis, and disseminated mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). All patients with active tuberculosis (TB) should also be tested for HIV. Consultation with a paediatric infectious disease specialist is recommended to assist in the management of these conditions.

HIV testing should also be considered for patients with certain laboratory results, such as unexplained, persistent lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia or anemia.

Possible clinical manifestations of HIV

- Failure to thrive

- Neurodevelopmental delay

- Recurrent bacterial infections

- Recurrent or chronic diarrhea

- Fever of unknown origin

- Generalized lymphadenopathy

- Thrush outside the neonatal period

- Opportunistic infections

Procedures

Testing methods

The HIV test of choice among children older than 18 months of age in Canada is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for HIV antibodies. This test may also be used before the age of 18 months if the birth mother’s status is unknown. In this scenario, a positive ELISA must be confirmed through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. Positive and indeterminate ELISA results are confirmed with Western blot testing. A false negative test may occur if the infection was acquired recently, within the last 2 to 4 weeks, the typical window period for developing HIV antibodies. If a high-risk exposure has occurred during that time period, a repeat test should be planned 1 to 3 months later if the initial test is negative. With that same time frame in mind, infants found to be breastfed by an HIV-positive mother should be tested 1 to 3 months after the cessation of breastfeeding.

Before the age of 18 months, children born to mothers living with HIV may have a positive ELISA due to the presence of maternal HIV antibodies. If the birth mother of a child in this age range is known to be HIV-infected, DNA and/or RNA PCR tests are the preferred assays for HIV diagnosis. In Canada, a qualitative HIV DNA PCR test (or combined qualitative DNA/RNA test) is standard in some regions, while others have adopted a quantitative RNA method. Infants born to mothers living with HIV should be tested with either assay at birth, at 1 month and at 4 months of age. A positive test at birth is generally thought to represent intrauterine infection. Both tests have 100% specificity by one month and 100% sensitivity by 4 months of age.14,15 Among infants receiving cART for prophylaxis, the quantitative RNA viral load may be suppressed to below the lower limit of detection, resulting in a false negative result until a few weeks after antiretrovirals are discontinued.

Pre-test counselling

Pre-test counselling should be provided before all HIV tests. The approach to counselling depends upon the age and developmental stage of the child being tested. For young children, discussion will take place with a parent or guardian. Developmentally age-appropriate adolescents who are able to provide consent for health care procedures should be counselled directly.

- Using a professionally trained interpreter is required for families who do not speak fluent English or French to ensure clear communication and confidentiality. The use of untrained interpreters, particularly children and adolescents, is not recommended. Families may be especially sensitive about sharing information about HIV diagnosis with an interpreter: make sure that the interpreter is acceptable to the patient’s family.

- The confidential nature of pre-test counselling should be clarified beforehand. However, it must be explained that HIV is considered a reportable infection by public health authorities.

- In scenarios of suspected perinatal HIV acquisition, it should be clarified that a positive test in the child will likely lead to a diagnosis of HIV in his or her birth mother.

- The meaning of a positive, negative or indeterminate test should be explained clearly, avoiding medical jargon.

- A history should be taken to identify any risk factors and their timing.

- The window period should be explained, along with the need for additional testing if the result is negative or indeterminate and a recent high-risk exposure has occurred.

- The psychological implications of a positive test should be explored, along with coping mechanisms and support systems for the patient.

- Finally, a follow-up appointment should be scheduled to provide test results and post-test counselling.

Post-test counselling

Post-test counselling is recommended for all test results. Issues of disclosure should be carefully considered for children found to be HIV-infected. In general, young children living with HIV are prepared over a period of several years for eventual disclosure, which is usually recommended to occur sometime between 10 and 12 years of age in developmentally age-appropriate children.16 Adolescents capable of providing consent for medical procedures should be told about their diagnosis after a positive result, with appropriate psychosocial support. Reactions of patients or their parents to a positive HIV test can vary, but it can be very difficult for them to hear. Individuals in distress should be referred to a mental health specialist immediately.

Post-test counselling following a positive test should include an educational component, to clarify the risks and routes of HIV transmission to others, how risks can be reduced, and giving specific guidance for transmission avoidance. Issues of disclosure to others should be discussed, with recommendations on how to prevent inappropriate disclosures of a child’s status. Finally, emphasize the availability of cART and the expectation of prolonged survival in good physical health on this therapy.

Breastfeeding

In Canada and other high-income countries, maternal HIV infection is considered a contraindication to breastfeeding.17 If a breastfeeding mother is known or suspected to have HIV, she should be counselled regarding the risk of transmission, advised to cease breastfeeding, and provided with an age-appropriate alternative form of nutrition for her child. These scenarios should be discussed with a paediatric infectious disease (ID) specialist, in case post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is indicated for the child.

A young child with possible HIV

Kay is a 22-month-old girl born in India, to Burmese parents who were living there as refugees. The parents, not Kay, have come to receive results and post-test counselling after HIV testing. Test results for both parents reveal that they are HIV-infected. In the examination room, Kay’s mother is breastfeeding her.

Kay has had no serious illness, and appears to be developmentally age-appropriate. Her weight is well below the 3rd percentile for her age, and she has small, palpable lymph nodes in the neck, axillae and groin. Otherwise her examination is unremarkable. Further history reveals that both parents were told they had a positive HIV test before arriving in Canada. Kay’s HIV test subsequently comes back positive.

How would you approach counselling these parents about testing their child, in addition to their own results? How would you approach the issue of breastfeeding?

Learning points:

- Pre-departure or post-arrival HIV testing is not routinely performed for immigrant and refugee children aged 0 to 14 years of age, regardless of country of origin.

- In India, when Kay’s parents were found to be HIV-infected, Kay was not tested. Her parents were responsible for communicating their results to a physician in Canada. In both countries, Kay was breastfed for several months following her mother’s diagnosis. This scenario should prompt immediate discussion with an on-call paediatric infectious disease specialist.

- If her parents had not been tested, HIV would still be a consideration in this child due to her failure to thrive and generalized lymphadenopathy.

Referral

All newcomer children found to be HIV-infected in Canada should be referred to a paediatric infectious disease specialist, and preferably to a paediatric HIV program. Each case should be discussed as soon as possible with an HIV clinician or paediatric infectious disease specialist at the local referral centre, to coordinate current management (e.g., initiation of PCP prophylaxis), and avoid delays with engaging the patient and family in care. If there is an ongoing exposure issue, such as breastfeeding, or the child has symptoms or signs consistent with HIV, the case should be discussed immediately with a paediatric infectious disease specialist on call.

Children living with HIV should be cared for by a multidisciplinary health care team, including a paediatric HIV specialist, nurse coordinator, pharmacist, dietician, clinical psychologist and social worker. The decision to start cART should be made by an HIV specialist, after consideration of the patient’s CD4 cell count and percentage, clinical history, and drug resistance profile. Long-term supervision of these medication regimens by a specialist is required. Although a discussion of antiretroviral regimens is beyond the scope of this document, up-to-date guidelines for managing HIV in children are available at the National Institutes of Health website.15

References

- UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), 2012.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Transfusion and risk of infection in Canada: Update 2012. Paediatr Child Health 2012;17(10):e102-11.

- Cotton M, Marais BJ, Andersson MI, et al. Minimizing the risk of non-vertical, non-sexual HIV infection in children – beyond mother to child transmission. J Int AIDS Soc 2012;15(2):17377.

- Gortmaker SL, Hughes M, Cervia J, et al; Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 219 Team. Effect of combination therapy including protease inhibitors on mortality among children and adolescents infected with HIV-1. New Engl J Med 2001;345(21):1522-8.

- Kapogiannis BG, Soe MM, Nesheim SR, et al. Mortality trends in the US Perinatal AIDS Collaborative Transmission Study (1986-2004). Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(10):1024-34.

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al; HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New Engl J Med 2011;365(6):493-505.

- Cooper ER, Charurat M, Mofenson L, et al; Women and Infants’ Transmission Study Group. Combination antiretroviral strategies for the treatment of pregnant HIV-1-infected women and prevention of perinatal HIV-1 transmission. J Acquired Immune Def Syndr 2002;29(5):484-94.

- Forbes JC, Alimenti AM, Singer J, et al; the Canadian Pediatric AIDS Research Group. A national review of vertical HIV transmission. AIDS 2012;26(6):757-63.

- MacPherson DW, Zencovich M, Gushulak BD. Emerging pediatric HIV epidemic related to migration. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12(4):612-7.

- Department of Justice Canada. Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2001. Available at http://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-2.5/.

- Citizen and Immigration Canada. Handbook for designated medical practitioners. Ottawa: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, 2011.

- Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E824-925. Appendix 6: Human immunodeficiency virus: Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees.

- Vermund SH, Wilson CM. Barriers to HIV testing—where next? Lancet 2002;360(9341):1186-7.

- Burgard M, Blanche S, Jasseron C, et al; Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA et les Hepatites virales French Perinatal Cohort. Performance of HIV-1 DNA or HIV-1 RNA tests for early diagnosis of perinatal HIV-1 infection during anti-retroviral prophylaxis. J Pediatr 2012;160(1):60-6.

- National Institutes of Health, Health and Human Services panel on antiretroviral therapy and medical management of HIV-infected children, 2012. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in pediatric HIV infection.

- Salter-Goldie R, King SM, Smith ML, et al. Disclosing HIV diagnosis to infected children: A health care team's approach. Vulnerable Children Youth Studies 2007;2(1):12-16.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Maternal infectious diseases, antimicrobial therapy or immunizations: Very few contraindications to breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health 2006;11(8):489-91. Updated 2011.

Editor(s)

- Michael Clark, MD

- Heather Onyett, MD

Last updated: January, 2014