Tuberculosis

Key points

- Of the 10 million new active tuberculosis (TB) cases worldwide each year, 95% occur in developing countries. In Canada, two-thirds of reported TB cases occur in foreign-born individuals, especially refugees from high-risk countries.

- The risk of TB is greatest in children younger than 5 years of age.

- Children new to Canada who are younger than 11 years are not required to undergo pre-arrival chest X-rays to detect TB in the lungs.

- Screening for TB in children and adolescents younger than 20 years is recommended to identify those infected and initiate treatment.

- A positive screening test should be followed by a chest X-ray to determine if there is active pulmonary disease. The majority of people infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis never become symptomatic or ill. They are said to have latent TB infection (LTBI).

- Treatment with anti-tuberculous drugs is given for different durations of time, depending on whether the patient has latent or active disease due to tuberculosis in the lungs or in other sites, such as bone or the central nervous system. Clinicians should consult with a paediatric infectious disease specialist for advice and potential referral of the patient, preferably someone with knowledge of anti-TB resistance patterns in the source country.

- Public health authorities must be notified of cases of latent or active TB.

- December 2015: Post-Arrival Tuberculosis Assessment of Syrian Refugee Children

Tuberculosis (TB) affects the lungs and other body tissues, and is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The infection is acquired by inhaling droplet nuclei from the respiratory secretions of people who have infectious pulmonary TB. Bovine TB, caused by the closely related M. bovis, can be acquired by consuming contaminated unpasteurized dairy products from infected cattle.

Epidemiology

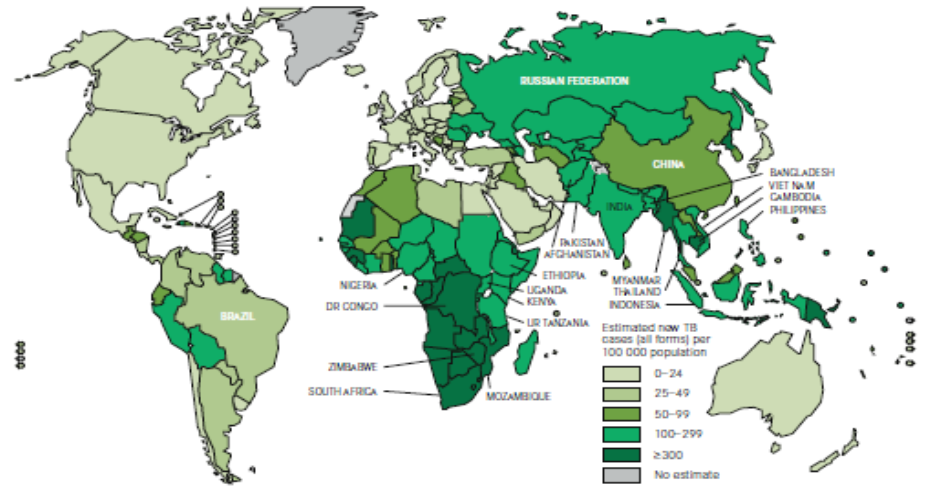

Although once thought to be on the decline, TB remains a major cause of death worldwide. Of the estimated 9 million new active TB cases each year, 95% occur in developing countries. In Canada, two-thirds of reported TB cases occur in foreign-born individuals.1 The risk of active TB in refugee populations is about double that of other immigrant populations.2

Figure 1. Estimated TB incidence worldwide, 2010

Epidemiological data for TB are provided on these websites:

- The Public Health Agency of Canada

- The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Early identification and treatment of people infected with TB, as well as their infectious contacts, is important to reduce the risk of transmission to others. Risk factors for TB are summarized below.

Risk factors for TB

- Contact with someone with infectious TB: Close contacts can include household members (parents, grandparents, teenage siblings, boarders), babysitters and other caregivers, visitors or other adults the child has frequent contact with, especially if they previously lived in a developing country with a high prevalence of TB.

- Recent (within the past 5 years) immigrant or refugee from country with a high prevalence of TB.

- Travel to a country with an increased prevalence of TB : Travel risks can include Canadian-born children visiting their parents’ country of origin or accompanying parents who work for international aid or trade organizations, and exchange students travelling to a developing country or region with an increased prevalence of TB.

- Immunodeficiency: Especially associated with infection with HIV/AIDS, but immunosuppression due to cancer therapy, daily steroid use or using immunomodulating agents such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors to treat chronic inflammatory conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and bowel disease), also increases risk.

Clinical clues

It is especially important to be alert to detect TB in immigrant and refugee children and adolescents new to Canada. Infants less than 1 year of age more frequently develop potentially fatal disseminated (miliary) TB and TB meningitis. Children and adolescents are likely to be asymptomatic with no observable clinical clues, except contact with a person who has active TB.

Clinical signs, when present, may include:

- Fever with night sweats

- Weight loss

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

- Meningitis, especially in infants less than 1 year of age

- Pneumonia that is unresponsive to commonly prescribed antibiotics in a high-risk child

- Gibbus of the thoracic vertebrae (Pott’s disease or osteomyelitis of the vertebrae)

Clinicians should be suspicious of TB in children and adolescents who have had the opportunity to contract it and/or present with one or more of the clinical signs. The age-specific risk for disease development after untreated primary TB infection is summarized in the table below.

Screening

In Canada, current recommendations advocate targeted testing of children at high risk for TB infection or progression of latent TB infection (LTBI) to TB disease (see Table 1).

Latent TB Infection (LTBI) is M. tuberculosis infection in a person who has a positive TST or IGRA, no physical findings of disease, a normal chest X-ray or evidence of healed infection (e.g, calcification in the lung, hilar lymph nodes, or both).3

Canadian Tuberculosis Standards recommend TB screening in children and adolescents younger than 20 years of age from countries with a high incidence of TB (30 per 100,000 for all forms of active TB cases) as soon as possible after arrival in Canada, using a tuberculin skin test (TST). If the results are positive, treatment for LTBI is recommended, after ruling out active TB.4

The Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) statement on Risk Assessment and Prevention of TB among Travellers recommends that children, particularly when they are younger than 5 years of age, be given priority for post-travel TB screening if they have had exposure to TB greater than routine tourist activities.

Targeted TB screening: Indications for the TST in children1

- Contacts of a known case of active TB

- Children with suspected active TB disease

- Children with known risk factors for progression of infection to disease

- Children travelling or residing for 3 months or longer in an area with a high incidence of TB, especially if the visit is anticipated to involve contact with the local population

- Children younger than 15 years of age who arrived in Canada from countries with a high TB incidence within the previous 2 years

TB infection diagnosis

Two diagnostic tests can be used to diagnose infection with M. tuberculosis: the TST and interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs).

Tuberculin Skin Test (TST)

The most common method used to diagnose children and adolescents1 infected with TB is the TST with 5 tuberculin units; the TST is also referred to as the Mantoux test. This test can be used in infants as young as 4 to 6 weeks of age. If the test result on a newcomer is negative, it should be repeated at least 2 months later to rule out incubating TB. A positive reaction may indicate infection with M. tuberculosis (see Table 2).

Note: For information on TST in adults, refer to the Canadian TB standards.1

Criteria for a positive TST (5TU-PPD*) in children and adolescents |

|

0 mm –4 mm induration is positive, if:

|

|

5 mm –9 mm induration is positive, if any one of the following risk factors is present:

|

|

≥ 10 mm induration is positive in all others |

|

*5TU-PPD = 5 tuberculin units of purified protein derivative Source: Canadian Tuberculosis Standards, 6th Edition. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2007. Reproduced with permission from the Minister of Health, 2012. |

A history of previous Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunization, no matter how recent, does not alter interpretation of the test.

If the test is positive, the clinician should:

- Request a chest X-ray to look for evidence of active pulmonary TB disease.

- Clinically evaluate the child for TB disease.

Further diagnosis of TB disease is discussed below.

Immunologically-based testing

Diagnosis of TB once depended solely on the TST, an imperfect test with known limitations. A recent advance has been the development of T-cell-based interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) for the diagnosis of M. tuberculosis. (IGRA tests include QuantiFERON-TB gold and gold in-tube, and T-SPOT).

These blood tests measure the in-vitro production of interferon-gamma by sensitized lymphocytes in response to M. tuberculosis-specific antigens. Some considerations:

- They may be more specific than the TST, and useful for evaluating TST-positive patients at low risk of latent TB infection (LTBI).

- They may add sensitivity if used in addition to the TST in immunocompromised patients, very young children and close contacts of infectious adults.

A discussion of the strengths and limitations of the TST and the IGRAs is available in the 2012 Red Book from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

The sensitivity of these blood IGRA tests is similar to that of the TST for detecting infection in adults and children with untreated, culture-confirmed tuberculosis. The specificity of IGRAs is higher than for a TST because the antigens used are not found in BCG or most pathogenic non-tuberculous mycobacteria. That is why the AAP notes that IGRA tests are preferred in asymptomatic children older than 4 years of age who have been immunized with the BCG vaccine.

The published experience of testing children with IGRAs is less extensive than for adults, but a number of studies have demonstrated that IGRAs perform well in children 5 years of age and older. Some children who received BCG vaccine can have a false-positive TST result, and LTBI is overestimated by use of the TST in these circumstances. The negative predictive value of IGRAs is not clear but, in general, if the IGRA test is negative and the TST result is positive in an asymptomatic child, the diagnosis of LTBI is unlikely. Children with a positive result from an IGRA should be considered infected with M. tuberculosis. Indeterminate IGRA results do not exclude infection with M. tuberculosis, may well necessitate repeat testing, and should not be used to make clinical decisions. Table 3 (below) summarizes AAP recommendations for the use of the TST and an IGRA in children.3

Two drawbacks of IGRAs are cost and availability. The test requires specialized tubes and procedures for the blood draw, and timely processing. The cost of IGRAs is not currently covered by provincial or territorial government-funded health plans in Canada, whereas the TST is covered. Patients or their families can choose to pay for the IGRA-TB test and would need to attend a centre where the test is available.

|

TST preferred, IGRA acceptablea:

|

|

IGRA preferred, TST acceptable:

|

|

TST and IGRA should be considered when:

|

| a A positive result for either test is considered significant in these groups.

b IGRAs should not be used in children < 2 years of age unless tuberculosis disease is suspected. In children 2 through 4 years of age, there are limited data about the usefulness of IGRAs in determining tuberculosis infection but IGRA testing can be performed if tuberculosis disease is suspected Source: Used with permission of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Tuberculosis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012:744 |

The major advantage of the TST is that the risk of active disease for different sizes of induration is well described, whereas very few prospective data exist for IGRAs. The major limitation of both tests is their inability to distinguish the 10% of people with LTBI infection in whom active TB will develop from the 90% in whom the disease will not develop.

TB disease diagnosis

If the screening test (TST or IGRA) is positive or there is doubt about interpreting results, the health care provider should consult with and/or refer to a paediatric infectious disease specialist or an expert in paediatric tuberculosis to determine whether the child or youth has latent TB infection or TB disease.

The clinician will also:

- Clinically evaluate the child for TB disease.

- Request a chest X-ray to look for evidence of active pulmonary TB disease.

- Request sputum cultures for TB if the chest X-ray shows evidence of active pulmonary TB disease. For a young child, who usually swallows sputum, the best culture material for the diagnosis of pulmonary TB is an early morning gastric aspirate.6 The sample requires rapid buffering to ensure viability of the organisms. However, the yield for finding TB organisms is low – it is cultured from less than 50% of children with pulmonary disease.

- Obtain cultures and additional tests from other sites of potential tuberculosis (i.e., cervical lymph nodes, meningitis, joints) in consultation with a paediatric infectious disease or TB specialist.

Positive cultures for M. tuberculosis confirm the diagnosis of TB disease. However, in the absence of a positive culture, diagnosis may be made on the basis of clinical signs and symptoms alone.

HIV testing in patients with TB

Because co-infection with HIV and TB may occur, HIV testing should be offered to all patients who have proven TB infection, as well as asymptomatic patients with a positive TST who have (or are suspected to have) risk factors for HIV infection.3 The duration of treatment for tuberculosis may be longer if the patient is HIV positive.

Physicians should give counsel and obtain informed consent before taking blood for HIV testing. It is also important to realize that in patients with active TB disease, results of the TST may be negative in HIV-infected patients who have an advanced degree of immunosuppression.

Published recommendations on testing for TB

- The Canadian Tuberculosis Committee made recommendations to the Public Health Agency of Canada in 2010 on the use of IGRAs to diagnosis TB5

- The Canadian Thoracic Society, Canadian Lung Association and the Public Health Agency of Canada recently updated guidelines on the treatment and diagnosis of TB.1

- The Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health has an evidence review on screening and treatment of TB in newly arriving immigrants and refugees.2

Treatment

If a case of latent or active TB is confirmed in a paediatric patient:

- The local Medical Officer of Health should be notified for contact-tracing.

- Consultation with and potential referral to a paediatric infectious disease specialist or a physician with expertise in childhood TB is recommended.

- Specific antituberculous treatment, based on the positive diagnostic test for latent tuberculosis (LTBI) or on defined sites of infection, should be started.

- Patients should be monitored at least monthly while on treatment for compliance and side effects. Although hepatotoxicity as an adverse reaction to anti-tuberculous drugs is less common in children than in adults, baseline liver function tests (alanine aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate transaminase [AST] and bilirubin levels) should be obtained before starting antituberculous therapy. Abnormal clinical or laboratory tests should be discussed with or referred to a paediatric infectious disease specialist or a physician with expertise in childhood TB. Importantly, parents should be told to discontinue medication and seek medical attention if anorexia, nausea or vomiting occur. They should also be provided with a clear plan of action – preferably written – with contact telephone numbers if symptoms occur.7

- Close family members, including parents, should be evaluated for active TB because they are the likely source – and are certainly a potential source – of ongoing transmission within and outside the health care institution.

Children with TB infection or disease can attend school or child care if they are receiving antituberculous therapy under medical supervision. Because children with primary TB are usually not contagious, their contacts are not likely to be infected unless they too have been in contact with the adult source.

Table 5 provides detailed information on the drugs used for treatment of Tuberculosis, daily and thrice weekly dosage regimens as well as principal side effects.

|

|

Daily dose (range) |

Thrice-weekly dose† (range) |

Available dosage forms |

Principal side effects |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

By weight (mg/kg) |

Max. (mg) |

By weight (mg/kg) |

Max. (mg) |

|

|

|

INH |

10 (10-15) ‡

|

300

|

20-30 |

600-900 |

10 mg/mL suspension 100 mg tablet 300 mg tablet |

|

|

RIF |

15 (10-20) |

600 |

10-20 |

600 |

10 mg/mL suspension 150 mg capsule 300 mg capsule |

|

|

PZA |

35 (30-40) |

2000 |

70 (60-80) |

* |

500 mg scored tablet

|

|

|

EMB |

20 (15-25) |

** |

40 (30-50) |

*** |

100 mg tablet 400 mg tablet

|

|

|

Pyridoxine (Used to prevent INH neuropathy: has no anti-TB activity) |

1 mg/kg |

25 |

|

|

25 mg. tablet 50 mg tablet |

|

| †Intermittent doses should be prescribed only when directly observed therapy is available. In general, daily therapy is definitely preferred over intermittent regimens.

‡Hepatotoxicity is greater when INH doses are more than 10 mg to 15 mg/kg daily. For older children and adolescents, the optimal dosing of INH is an area of uncertainty *For PZA: 3000 mg according to the American Thoracic Society, 2000 mg according to the AAP's Red Book**For EMB: 1600 mg according to the American Thoracic Society, 2500 mg according to the AAP's Red Book ***For EMB: 2400 mg according to the American Thoracic Society, 2500 mg according to the AAP's Red BookSources: Kitai I, Demers A. Pediatric tuberculosis.(in reference 1),3,8,9. |

||||||

Using steroids to treat TB

In addition to the antituberculous therapies detailed above, steroids are useful when host inflammatory response is contributing to specific tissue damage or dysfunction. Steroid use in meningitis may decrease neurologic complications and death. Steroids may also benefit patients with miliary (disseminated) disease or endobronchial disease resulting in airway obstruction and atelectasis.

Prevention

A number of strategies can help prevent TB disease among immigrant and refugee children and adolescents new to Canada. These include:

- Screening: Do not assume that children have been screened for TB before admission to Canada. Children younger than 11 years of age are not automatically screened for TB with a chest X-ray before admission to Canada.

- Testing: Test all immigrant or refugee children for TB who are from an endemic area upon arrival in Canada, using the TST or IGRA. If the test is positive, refer to the previous sections on diagnosis, treatment and contact-tracing. If the initial TST is negative, it should be repeated at least 2 months after arrival to rule out incubating TB. The TST can be used for children as young as 4 to 6 weeks of age.

- Compliance: As part of prevention, health professionals should do more to ensure compliance with recommended TB therapy: to eradicate infection and to prevent both the spread of infection to others and the development of drug resistance.

Immunization with the BCG vaccine is controversial. This vaccine of live attenuated strains of M. bovis is given at birth in developing and many developed countries with a higher prevalence of tuberculosis than in Canada as part of the WHO’s Expanded Programme on Immunization. BCG vaccine efficacy is estimated to be about 51% in preventing any TB disease and up to 78% in protecting newborns from miliary (disseminated) or meningeal tuberculosis. Currently, BCG vaccine is given to infants in Nunavut because of a high incidence of infectious TB. BCG vaccination is not recommended for routine use in any other Canadian population.10 Developing more effective vaccines to prevent TB is a global health priority.

A child with positive screening test for TB

Alex is a 4-year-old boy who has had a positive skin test (the Mantoux test) to screen for tuberculosis. His family have immigrated from Belarus. His parents' English is still very limited. Alex attends junior kindergarten.

Isoniazid treatment was recommended after further assessment was normal and a diagnosis of TB infection was made. However, Alex's parents initially declined treatment because they did not understand the reason for treatment. In Belarus, only people with symptomatic tuberculosis are treated with drugs, not those with a positive Mantoux test.

Challenges:

- How would you tell the family that, because of his abnormal screening test, Alex’s case needs to be reported to the local public health department?

- How would you explain to his parents that the public health department will require all family members to be assessed for possible infection with M. tuberculosis?

- How would you explain that although Alex is not sick, Canadian recommendations are for a course of prophylactic antituberculous medications to prevent him from becoming ill with TB in the future?

Key points:

- Treatment practices in other countries are often different from those in Canada.

- In Canada, a positive tuberculin skin test in a child requires notification of the local public health department, which will coordinate further assessment of the family for possible tuberculosis disease.

- Alex’s health care provider needs to spend time with his parents, with an interpreter if possible, to help them understand the benefits of receiving antituberculous medication, for Alex as well as other family members who may be diagnosed with tuberculosis. Infectious disease or TB clinics are available in most regions to help provide care and answer a newcomer family’s questions.

Selected resources

Additional reading

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis (TB).

- Greenaway C, Sandoe A, Vissandjee B; Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health, et al. Tuberculosis: Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E939-51.

- Kakkar F, Allen UD, Ling D, et al. Tuberculosis in children: New diagnostic blood tests. Paediatr Child Health 2010;15(8):529-33.

- Menzies D, ed. The Canadian tuberculosis standards, 7th edn. Ottawa: Canadian Thoracic Society/Canadian Lung Association and the Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014.

Useful links

- TB Germ, A Cunning World Traveller: An easy-to-understand video produced by the BC Lung Association and the BC Centre for Disease Control. Suitable for both adults and older children. Available in Mandarin as well.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Tuberculosis prevention and control.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis.

References

- Menzies D, ed. The Canadian tuberculosis standards, 7th edn. Ottawa: Canadian Thoracic Society/Canadian Lung Association and the Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014.

- Greenaway C, Sandoe A, Vissandjee B; Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health, et al. Tuberculosis: Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183(12):E939-51.

- Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012.

- Greenaway C, Khan K, Schwartzman K. “Tuberculosis surveillance and screening in selected high-risk populations”. Canadian Tuberculosis Standards, 7th edition, 2013. Canadian Thoracic Society and Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014.

- Canadian Tuberculosis Committee. Recommendations on interferon gamma release assays for the diagnosis for latent tuberculosis infection – 2010 update. CCDR 2010;36(ACS-5):1-22.

- Curry International Tuberculosis Center. Pediatric tuberculosis: A guide to the gastric aspirate procedure.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe isoniazid-associated liver injuries among persons being treated for latent tuberculosis infection - United States, 2004-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59(8):224-9.

- World Health Organization. Rapid advice: Treatment of tuberculosis in children. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2010. Report no.: WHO/HTM/TB/2010.13.

- Blumberg HM, Burman WJ, Chaisson RE, et al. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: Treatment of Tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167(4):603-62.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canada immunization guide: Evergreen edition, 2012. See Pt. 4, Active vaccines, Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine.

Other works consulted

- Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, et al. The clinical epidemiology of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: A critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8(3):278-85.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Tuberculosis in Canada 2010, Pre-release.

- WHO. Global tuberculosis control 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2011.

Editor(s)

- Heather Onyett, MD

Last updated: February, 2023